Note: this week’s essay contains a lot of historical photos I’ve found, so it will likely not fit in your email – just click the link at the end of your email to read the entire essay, or just go here to read it online.

Last week I wrote about how giant sequoias survive wildfires, or at least, how many of them do, since some conflagrations are just too hot for the trees to withstand. I was still curious about how so many of them were logged back at the turn of the last century – once we saw how enormous these trees are (big enough to live inside and shelter horses), we immediately wondered how loggers maneuvered them into sawmills and moved them up and down hillsides. What was sequoia wood used for? Just how long did it take to cut down a giant sequoia when chainsaws didn’t yet exist?

How were giant sequoias logged?

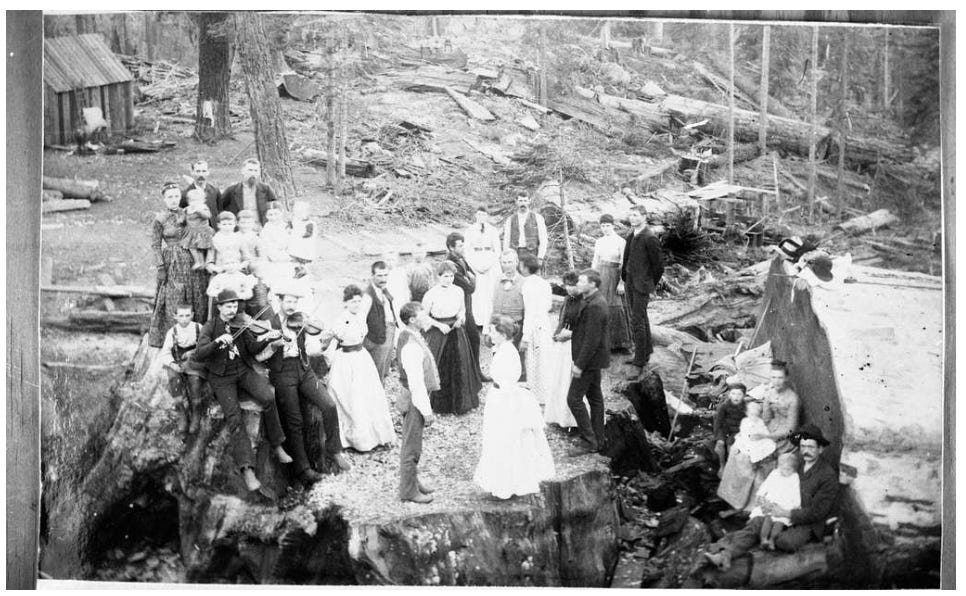

We took the photo at the top of this essay at Stump Meadow, an isolated area off a dirt road in what was the Converse Basin, one of the main logging areas for the Kings River Lumber Company. All that remains now are hundreds of stumps rotting in a meadow that’s slowly turning back into forest.

Over 100 years ago, about 8,000 giant sequoias were cut in this area and moved to the mill, which was perched beside the creek among those tall trees (young sequoias) in the background. Of course, those young (100-year-old) trees didn’t exist back in that day, as the landscape had been razed to bare dirt and stumps:

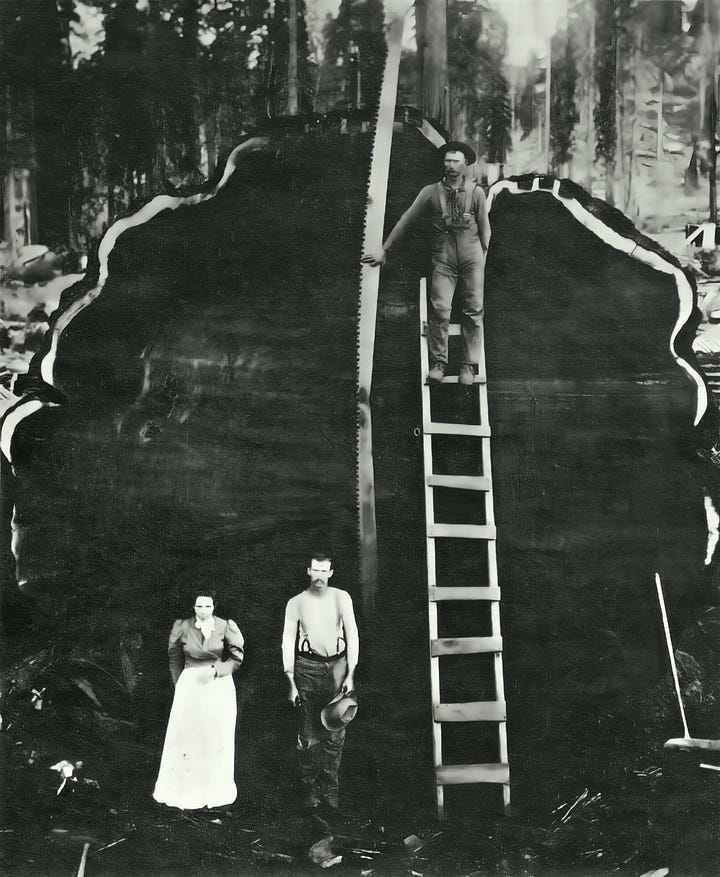

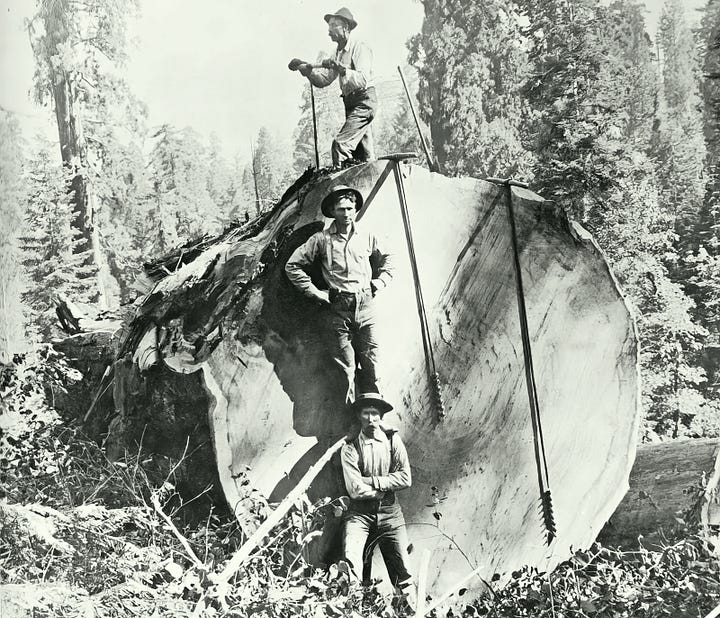

Once the Gold Rush brought slews of people pouring into the region, it was inevitable that someone would stumble upon the forests of giant sequoias. In 1852, a bear hunter named Augustus Dowd discovered the North Grove and the enormous Discovery Tree. That tree later took five men 22 days to chop down.

If a tree takes weeks to cut down, you’d think it would give you pause about whether you were doing the right thing. But we can’t underestimate the hubris of man and the power of Manifest Destiny.

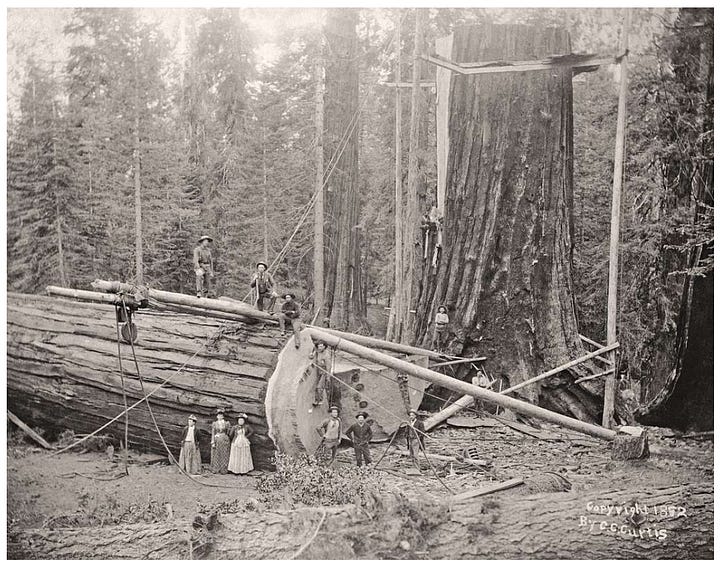

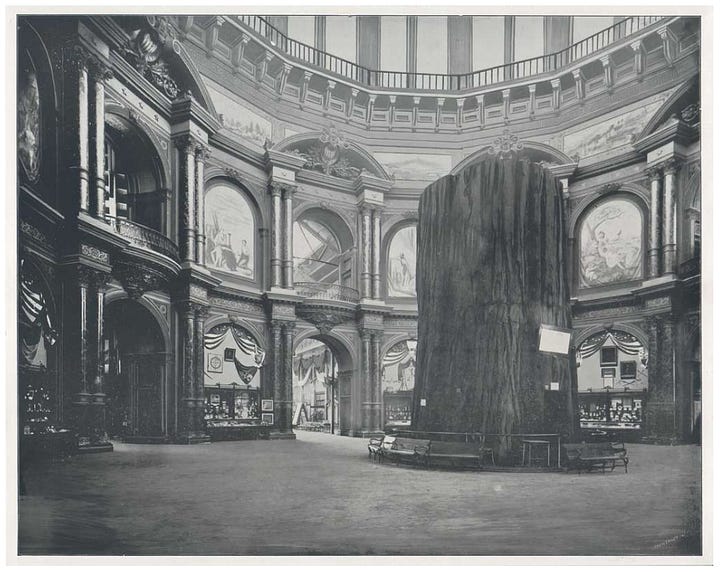

At any rate, these men saw dollar signs and proceeded to tackle the arduous task of felling a massive beast taller and heavier than most buildings they’d previously encountered. Tales of these enormous trees began trickling back to the east coast, but no one believed them. So, one group dismantled the General Noble tree and sent it back east to the World’s Fair (side note – if you find trees large enough that you feel the urge to name each one before cutting it down, might that also be a sign that perhaps you should reconsider?):

I can’t begin to imagine the sound these giants made when the final ax chop was made and they began to tilt through the forest canopy. Literally tons of wood fell hundreds of feet, shaking the earth when it landed.

Hank Johnston, author of They Felled the Redwoods, describes it poetically: “Dust and debris filled the air. The great stump, relieved of its burden of centuries, quivered for many minutes in a series of paroxysmal reactions. The ground trembled and shook as if struck by a mighty earthquake. A life, several thousand years in the making, had been snuffed out in a moment.”

And here’s what I found to be one of the more tragic parts of the story: sequoia wood is brittle, much more so than coastal redwood. Meaning, about half or more of the giant trees exploded when they fell to the ground, shattering into splinters. Loggers tried padding the ground with branches, with little effect. When a tree shattered like this, it was left to rot while the crew moved on to another tree.

I actually felt nauseated when I read this.

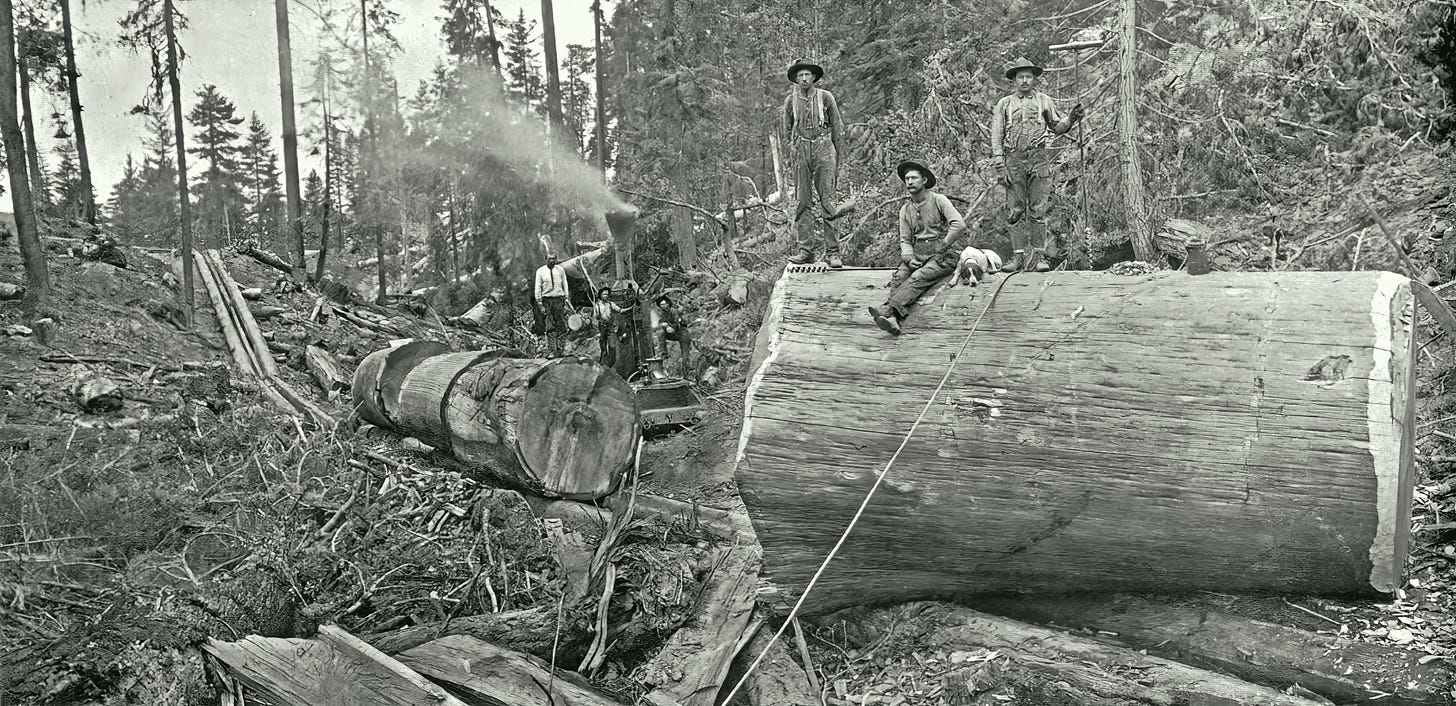

For those sequoias that stayed intact, once the tree was on the ground, the work had just begun. What do you do with a 250-foot-long log that’s 15 feet in diameter? It’s too big for horses or oxen, which was what loggers used on the east coast when clearcutting what would become the Great Smokies National Park. So instead, they cut the logs into sections or split them by inserting black powder and blasting them into sections:

The sections were then dragged using a “steam donkey,” a type of winch connected to cables. The logs ran along chutes made of smaller logs that had to be greased to prevent the friction from causing a fire.

Once at the mill, the logs were cut by a 90-foot bandsaw, the largest in the world. The wood was then hoisted up and over the mountain on railcars to the town of Millwood, where it was cut into boards and stacked to dry.

But the wood still had to get to civilization where it could be used, and for that they used a 54-mile-long flume that took the wood to Sanger, California. Built on trestles, the flume carried bundles of planks along a V-shaped flume, sometimes at up to 50 mph. The flume was also used as transportation for workers downstream to Sanger.

As you can imagine, all these hoists, chutes, flumes, and multiple mills were not cheap. It cost money to kill these trees – lots of money. The Converse Basin grove of sequoias changed hands several times between different lumber companies as each tried to break even. More trees were cut in an effort to chase down profits, but in the end, no one really got rich off sequoia wood. Because of its brittleness, the wood was mainly used for fence posts, shingles, matchsticks, and pencils.

The Converse Basin was eventually sold back to the federal government to become part of the Giant Sequoia National Monument, though it has not recovered despite attempts at restoration. Scientists are studying why Stump Meadow continues to resist regrowth and remain a grassy opening, with one theory being that the massive number of removed trees made the water table rise and prevented regrowth.

I realize it’s pointless, but since visiting the sequoias I have wondered what the forests all across America would look like had the lumber boom not happened. Walking among the trees of our local forests, they all seem to be youngsters, so much spindlier and sparser than the oldsters that were taken down a hundred years ago. Even here on the east coast we had giant poplars, grandfather trees that had filled the forest for centuries. It’s hard to believe they’re all gone. At least someone (John Muir and others) had the wherewithal to protect the giant sequoias in the Sierra Nevada before the final ones could be made into matchsticks.

Weird Nature:

Hummingbird bathing in a sprinkler (click to watch):

Great Story. Having lived on the Olympic Peninsula, I knew about the massive logging operations but never thought about the economics or how a changed ecosystem might not return to it's previous state. This is a pathetic reminder of the consequences of human impacts on natural resources. See my recent story about oysters.

https://ecologistatlarge.substack.com/p/25-14-the-incredible-edible-oyster