How do giant sequoias survive wildfires?

Part 1 exploring the many questions I had while visiting them…

Last week I walked in a forest of giant sequoias. It is impossible to communicate just how enormous these trees are until you find yourself at their solidly-planted feet and look up into the branches hundreds of feet above. Andrew suggested the only way to explain their enormity is to imagine a school bus, sitting vertically on its rear end, then bundle two more school buses with it – that’s the base of the tree. Then, of course, you’ll have to pile even more school buses on top of those, because sequoias don’t really taper – they’re wide and thick right to the top, where their stubby top branches suddenly branch out to cover their oftentimes bald heads.

Seeing these enormous giants prompted lots of questions: Why are sequoias so wide all the way to their tops? How did loggers cut them down without chainsaws back in the 1800s? How did they transport an object the size of multiple school buses and saw them into lumber? What was the wood used for and do we still log sequoias? Do any still exist outside of protected areas?

And then we drove through this:

This is what’s left of the Redwood Canyon fire that burned up over 2,000 giant sequoias in a months-long fire in 2021. It’s one of the reasons we chose to visit sequoias over coastal redwoods – giant sequoias are considered more endangered because of wildfires.

Many of these majestic trees obviously did not survive. But oftentimes sequoias do survive, and they actually need fire to thrive. Why is that?

How do giant sequoias survive wildfires?

Andrew and I flew five hours to San Francisco and then drove back east through the almond orchards and orange groves of Central Valley towards the Sierra Nevada mountains. Sequoias are only found on the western slopes of these snowy peaks at around 4,000-8,000 feet in elevation. However, giant sequoias are not everywhere you look – they occur in groves, about 80 of them, each with a name and a carefully noted location on the map. They are endangered, after all. They actually used to be more widespread, living all over North American and as far away as Australia and New Zealand before the last Ice Age.

As we drove through Yosemite and then later Sequoia National Parks, we encountered plenty of “young” sequoias that just looked like regular, albeit large, trees. Sequoias grow really quickly: by the time one is 50 years old it can be 100 feet tall and 8 feet in diameter, meaning it grows an average of 2 vertical feet per year. Once a sequoia has raced upward to a respectable height, it begins to grow outward at a rapid rate and continues this throughout its lifetime. It’s why sequoias end up looking like rocket ships in the midst of a forest of more slender trees – they bulk up and grow outward at a greater rate than other trees. It’s also why giant sequoias are the largest trees in the world by volume – coastal redwoods are taller but thinner.

To put this growth in perspective, the General Sherman tree is considered to be the world’s largest tree but also the fastest growing. It is 272 feet high and over 100 feet in circumference – if the tree grew a millimeter of new bark each year over its entire surface area, that new wood is enough to build a 5-6 room house every 40 years.

The giant sequoia’s bark has a lot to do with why it survives fires. The outer bark is extremely thick – about 18 inches of fibrous bark protects the cambium layer underneath. The tannic acids within the bark also make it resistant to fires. Almost every tree we saw had fire damage to its base – these trees were over 1,000 years old and had lived through many fire events. In the picture above I’m standing next to an unnamed tree (meaning it wasn’t even one of the larger specimens, which were mostly named for presidents and were fenced off to keep visitors at bay). This particular tree was overwhelming – looking up along its trunk, through the crevasses of its bark, it felt like standing beside a living building. When I knocked on its bark, it sounded almost hollow, and looked lightweight and similar to the shell of a coconut. That was not true of the bits of heartwood that were exposed and extremely dense and hard.

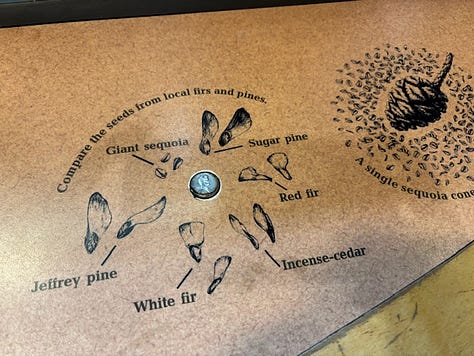

When a low-burning fire creeps through the forest and burns up any underbrush, it leaves the ashy, open forest floor that sequoia seedlings thrive in. The cones need the heat of the fire to open, either when on the ground or from warm air wafting up into cones in the branches above.

However, for many years in the early days of the Forest Service, we unfortunately did not understand the sequoias’ adaptation to fire. Forest fire suppression led to the buildup of extremely high fire loads – old branches, thick undergrowth, and many years’ worth of dead trees piled up on the forest floor. When lightning struck, the whole tinderbox went up in flames that were too hot for the sequoias to resist, even with their thick bark.

This is partially what led the Redwood Canyon fire to become so large – a combination of lack of prescribed burns along with drought that caused trees to become susceptible to pine beetles in the years beforehand. The KNP Complex fire that burned Redwood Canyon was the result of a lightning strike and two separate wildfires joining to create one bigger one. You may remember the efforts to protect General Sherman by wrapping it in reflective material and setting up sprinklers nearby:

The park service also wrapped up historic cabins in a successful effort to protect them for us to find several years later:

Nowadays the forest service sets up controlled burns as well as clean-up operations where they scrape the forest floor down to the soil, creating optimum breeding ground for the tiny seedlings. Andrew and I saw both of these conservation efforts in action as we hiked.

While we now understand that sequoias require regular, low-burning fires to survive, that doesn’t mean the trees are now safe. There are acres and acres of forests that are cluttered with deadfall that could explode into massive fires. Now that the park service and Forest Service have fewer employees due to reductions in force, I’m sure that will impact their ability to clear the forests in preparation for prescribed burns.

I sincerely hope we can protect these trees and preserve them for the future. They’re too important to disappear.

This newsletter is already running long and I haven’t even started talking about their logging history, so I will save that until next time.

What are your thoughts about these magnificent trees? Have you visited them? What was your experience?

After living in California as an exchange student for a year in the 90s I brought my family back in 2017 and we visited Kings Canyon and Sequoia National Park. We were absolutely awestruck - it's really hard to put into words what it feels like to walk amongst giant after giant tree. We have a family photo up of us all posed by the base of General Sherman - all grinning!