Wood that won’t float? Trees that won’t rot?

Why doesn't Nature follow the rules?

Welcome to Natural Wonders, where I ask many random, useless questions and occasionally provide a service by researching helpful questions such as Does fingernail polish really kill chiggers? and Why are some people allergic to poison ivy and others aren’t? Read on for this week’s installment of random uselessness…

One year when I taught first grade and we were in the midst of our sink and float unit, I mentioned to my students that my dad had brought me a rock that floated. Years earlier he had paddled the Colorado and found a natural pumice stone on a riverside beach. Pumice is an igneous rock that forms when lava cools rapidly and collects bubbles inside that allow it to float when hardened. My students were amazed to hear that a rock could float, none more than little Jamie. He begged me to bring it in so he could see it float with his own eyes.

Sure enough, the next day I brought it in and held it in my hand for the class to see during morning meeting. Jamie was very quiet and not nearly as enthusiastic as the day before. When I questioned him about it his face sagged. “I thought you meant it floated in the air,” he murmured and turned away.

Six-year-olds can be hard to impress.

As adults, we think we’re pretty sure about which objects float and sink – it seems like a very basic concept. But many people I know are impressed by a rock that can float (in water) and assume they know the fundamentals of buoyancy – rocks sink, wood floats, and that’s that, right?

Is there a wood that DOESN’T float?

When I went on hikes with my family as a child, my dad used to point out a particular tree he called Ironwood. It has a very muscular-looking trunk and, not surprisingly, is also called Musclewood. It is one of the few trees that is so dense it won’t float.

Ironwood is a midstory tree that tops out at about 40 feet. When I went looking for sample trees on a hike with Toby, I only found them within 20 feet or closer to running water – they love moist areas. It was easy to confuse them with beech trees because their leaves look almost identical, just smaller, and their bark is very similar. But it’s the muscularity of the trunk that makes it stand out.

The Latin name for this tree is carpinus caroliniana and it’s commonly called an American Hornbeam. Actually, “ironwood” is a nickname for this tree and when I looked up that term I found there are at least 163 different trees with Ironwood in their name. It turns out people all over the world tend to call heavy, dense trees after the heaviest metal they know.

Not all of these trees necessarily sink in water, however. The density of wood is measured in cubic feet – if a cubic foot of wood weighs more than a cubic foot of water, that wood will sink. The more space for air inside the trunk, the less dense the wood is. Trees that have thick sap tend to have more gaps in the sapwood and thus hold more air once they’ve fallen. Dense trees tend to have thin, watery sap that travels through tiny pores inside the trunk, leaving less room for air pockets. Many of the dense trees I read about live in the hot, desert climates of the western U.S. or in the dry climates of Africa.

The densest tree in the world is Black Ironwood, a type of olive tree in sub-Saharan Africa. A cubic foot of it weighs 84.5 pounds, and since a cubic foot of water weighs 62.4 pounds, this ironwood will obviously sink.

What about my American Hornbeam ironwood trees? Will they sink? I couldn’t find any fallen branches beneath the trees I encountered on my hike (I really wanted to test a piece!). However, my research shows American Hornbeam trees weighing around 45 pounds per cubic foot, which means it should float.

It looks like if I want to find a true sinking ironwood in the United States, I’ll have to head to the Sonoran Desert to see the Desert Ironwood, which weighs in at 75 pounds per cubic foot. Too bad there’s likely no water nearby to watch it sink…

Wood that doesn’t rot?

Speaking of the counterintuitive behaviors of trees, what about wood that won’t rot? My brother recently made a couple benches for his fire pit area from a black locust tree to replace two other benches that rotted over time. Old timers say if you build it out of locust, it won’t rot – is that true?

This is nature folklore that turns out to be true – the heartwood of a black locust contains robinin, a natural preservative that helps it resist rot and insect damage. It’s often used for fence posts and outdoor furniture because it won’t rot, even in wet ground.

When my friend Beth and I ate at Alley’s Ol’ Store the other day (highly recommend if you’re near Tallulah Gorge in Georgia), I noticed these locust pillars holding up the porch and asked the owner how old they were. She said they were original, which meant they were installed 98 years ago when the store was built.

I was amazed by that until I found out the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal used locust for its locks and aqueducts – the wood is still in use today, 150 years later. And there’s a black locust split rail fence at George Washington’s Mount Vernon that is 200 years old. This wood lasts!

Better yet, locust wood is actually impervious to carpenter bees! If you’ve ever hunted carpenter bees on your porch with a tennis racket, you know how big a deal this is. Building a deck out of locust wood means your deck would still be there (free of carpenter bee holes) more than 100 years from now.

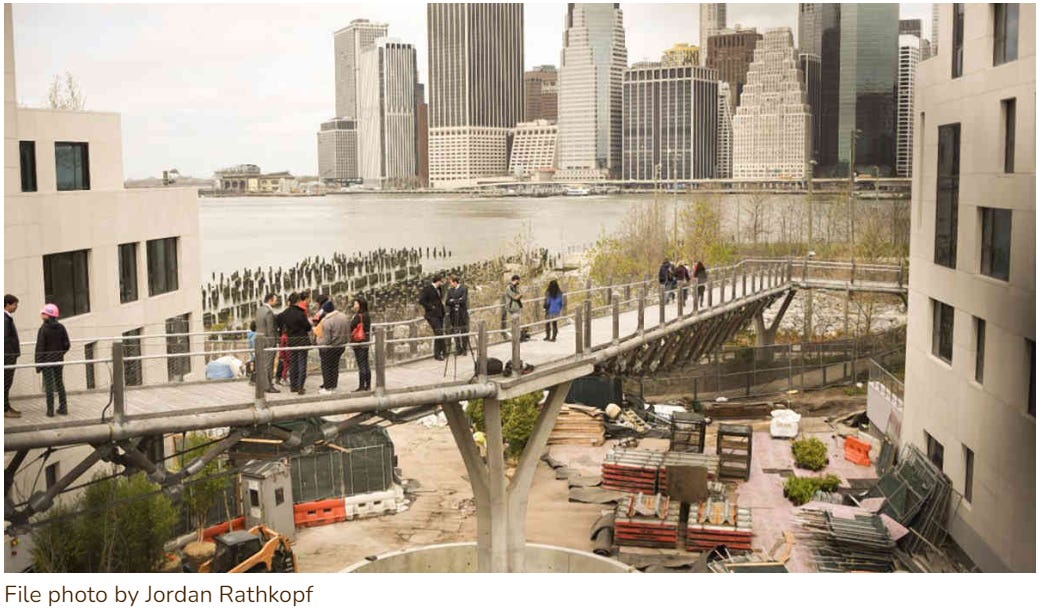

That’s probably what folks in Brooklyn thought when they built a pedestrian bridge out of black locust a few years ago. For some reason, that bridge DID start to rot and has had to be removed.

It turns out it was likely installed incorrectly without being allowed to expand and contract with the weather. It also wasn’t dried correctly beforehand. It caused a multi-million-dollar kerfuffle and gave a bad name to black locust wood, which at least one guy is trying to defend.

Somehow, city architects were not able to succeed where George Washington and builders of old country stores had. I’m sure there’s a lesson to be had there.

Plant Highlight: Mountain Laurel

Mountain Laurel is a tall evergreen shrub that blooms prolifically with wet spring/winter weather. The flowers, when closed, appear pink and then fade to white as they open. The flower stamens have a nifty, spring-like action that sprays pollen when a bee lands inside.

All parts of this plant are poisonous, however, so no munching on the leaves or flowers. The Forest Service says, After initial consumption, the victim will experience burning lips, mouth, and throat, followed six hours later by nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, low blood pressure, drowsiness, convulsions, weakness, and progressive paralysis followed by coma and death. Even honey made from the flowers is toxic. Yikes!

Weird Nature:

Detritus (newsletter recommendations):

North Carolina Rabbit Hole is a wonderful newsletter with all kinds of North Carolina trivia and history, including this fascinating story about how Carolina panthers aren’t real…

This frog is a terrible jumper (but the newsletter this story comes from is great!)

I never knew what a songbird fallout was until I read this newsletter, which linked to these amazing pictures from a fallout that occurred in 2011 at the Machias Seal Island lighthouse.

Sure enough, New Zealand has a tree with the common name ironwood (although that name is seldom used, it's normally called maire). Interestingly, it's a relative of the black ironwood of Africa.