Welcome to Natural Wonders, a newsletter that explores marvels of the natural world such as the mood-lifting power of waterfalls and how to check the not-dead status of local fauna. If you’re new here, you can subscribe below and see what this newsletter’s about here.

I have a complicated history with poison ivy. I have gotten poison ivy rash too many times to count since I was a kid. It seems like I can just look at the plant and get it. As a matter of fact, I will probably end up with itchy hives simply because I’ve spent the past few days marinating in the research about poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac.

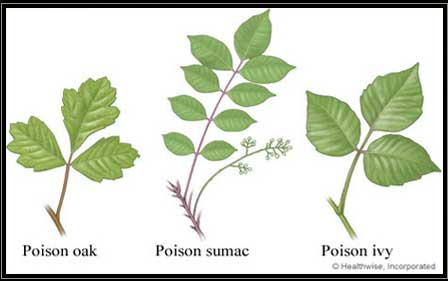

For those lucky enough not to know what I’m talking about, poison ivy is a three-leafed plant that contains an oil that causes an incredibly itchy rash lasting for weeks. People have a reaction after brushing up against the plant or by simply touching something else – a tool, a glove, your dog – that has the oil on it. I have spent weeks getting the poison ivy rash over and over, only to find out my shoes had the oil on them. Even worse, if you burn wood that has remnants of the vine, breathing the smoke can cause a rash in the throat and lungs.

I got a bad case of poison ivy in college when I helped Andrew stack a load of firewood that evidently had dead ivy vines on the outer edges. I brushed my face with my gloves and ended up with swelling near my eyes treatable only with cortisone shots.

At a wild foods clinic one spring during college, I was told that eating a tiny poison ivy leaf the size of my pinky fingernail would help immunize me against getting rashes in the future. I was desperate enough that I tried it.

Didn’t work.

I got an extremely bad case of poison ivy that weekend, probably exacerbated by slicing open my legs while walking through tall grass and immediately getting into poison ivy. For the next six years, I got poison ivy every spring, whether I’d been near the plant or not.

All of that time, Andrew never got poison ivy. He’d helped stack the firewood, he biked and hiked in most of the same places I did (he didn’t eat a leaf, however) – so why was he seemingly immune when I was not? What’s so special about him?

Why are some people allergic to poison ivy and others aren’t?

There are three main plants that cause this rash, but for simplicity’s sake I’m going to mainly refer to poison ivy from this point forward because they are all very similar in appearance and effects. These plants contain an oil called urushiol which is also present in mango rinds and cashew shells as well as Japanese lacquer trees. It only takes one billionth of a gram of the oil to cause you to breakout. This stuff is so volatile that a quarter of an ounce (7 grams) is all that’s needed to cause a rash for every person on Earth. Urushiol is only dangerous to humans – plenty of birds eat the berries, and other animals, such as deer and rabbits, eat the leaves and stems.

Despite the name, the oil is not a poison. It’s an allergen – your body’s response is an allergic reaction. When we brush up against the leaf, our bodies produce antibodies, which then produce histamines, which expand blood vessels under the skin. But when too much histamine is produced, it results in a rash and swelling. You scratch it, opening wounds, and potentially cause infection. In reality, your body is causing damage to itself because your immune system is going haywire.

This is what happens with the 85% of people who have a reaction to poison ivy. The other 15% of people simply have an immune system that doesn’t react to the oil. They have a non-haywire immune system.

However, if you’re one of these lucky people, don’t get too comfortable. Our immune systems change as we get older. Some people may react less dramatically to urushiol as they get older (please let that be me!) while others who have never had a reaction may begin to break out into a rash. That might explain why Andrew suddenly got a poison ivy rash a few months ago for the first time in his life. It is possibly the beginning of a new sensitivity to the oil.

The more you “catch” poison ivy and get a rash, the more likely you are to be sensitive in the future and the more severe your reactions will become. This is because you’ve primed your immune system to react to the “threat” of urushiol. This is probably what happened to me – over the course of just a few years in college, I got several bad cases. Each time they seemed to get a bit worse as my immune system overreacted to repeated exposures.

Of course, my eating a leaf didn’t help the situation. My research shows it is NOT recommended that you eat a leaf with the word “poison” in its name. As you might imagine, side effects include possible severe reactions or even a rash in your throat. I can’t even imagine…

So, if eating a leaf doesn’t help desensitize you to the effects of poison ivy, what does work?

On a recent hike at a state park, I noticed these bee hives directly beside a large patch of poison ivy. Does this mean the bees could forage for nectar in the poison ivy flowers? Some of the plants had flowers almost ready to bloom:

Would honey made from poison ivy blossoms be a bad thing or a good thing? I can imagine both scenarios – I could develop an itchy rash in my throat from eating the honey with my biscuits or I might get a boost to my immune system in the same way that local honey supposedly can help with allergies. Well, it turns out that eating local honey actually doesn’t help you with allergies. So that’s the bad news. But the good news is the nectar from poison ivy flowers doesn’t contain the urushiol oil, so the bees never bring it back to their hive. It’s safe to eat, but it’s not going to help cure your poison ivy allergy, either.

Unfortunately, right now there’s not a good solution. A study in 2016 identified a specific protein in the immune system that causes the dermatitis and scientists were able to block that protein in mice, reducing their itching. But it has not been tested in humans yet. Another group of scientists found that exposing subjects to urushiol using a patch (presumably similar to a Nicotine patch) over three or more months resulted in reduced sensitivity to the oil.

It seems like your best bet is to avoid the plant in the first place. The common saying is: Leaves of three, let it be. Even if you’re one of the 15% of people who doesn’t have a reaction, it doesn’t mean you’re immune. It likely means you haven’t had a reaction YET.

Verdict: people who aren’t allergic to poison ivy probably A) have not had any/much exposure to the plant in the first place, so their immune systems haven’t learned to react, or B) have immune systems that will change over time and become susceptible to urushiol oil.

Interesting facts:

While honey made from poison ivy blossoms isn’t dangerous, there are some honeys that are considered toxic. The blossoms of rhododendrons contain a toxin that is bad for bees. The pollen from buttercups causes bees to become paralyzed and die. And mountain laurel is toxic to bees, humans, and livestock, but the honey produced by its pollen is so bitter it’s unlikely to be eaten.

Urushiol oil can remain active for over a year – so wash those old gardening gloves!

People who are allergic will break out in a rash within 24-72 hours of exposure. But if it’s your first exposure, it could take 7-10 days to break out as your immune system processes the information and tries to decide what to do. This may lead some people to think they’re immune when it’s simply a delayed reaction. Some people don’t have their first reaction until they’ve been exposed multiple times.

Sensitivity to poison ivy is genetic – if your dad is allergic, chances are you will be too.

Settlers in America enjoyed the gold and red leaves of poison ivy in the fall and so sent it back to Europe to be transplanted into the gardens of emperors and kings as a decorative plant. You’re welcome.

Poison ivy sap can be used to make indelible ink.

Scratching the rash doesn’t make it spread – and you can’t give your friend the rash if they accidentally touch you.

If you do get a rash, use a hairdryer on it for as long as you can stand – it feels as if you’re scratching it and relieves the itching for several hours. Other friends and family have recommended shoe polish to dry up the rash, anti-itch clear lotion, and these pills, which I’ve been taking as a preventative since I was exposed two days ago, and so far it’s working…

What’s your experience with poison ivy, oak, and sumac? Have you gotten a bad reaction before? Anybody else crazy enough to eat a leaf? Join the conversation below:

Weird Nature:

A few weeks ago I wrote about invasive worms - here’s a video of one of the Asian Jumping Worms:

If you liked this issue, please click the “like” button below - it helps raise the profile of the newsletter so it’s easier for other folks to find it.

The urushiol oil chemically bonds to the skin so it is not removed by soap. However, detergents will break the bonding and remove the oil. If you suspect that you have been exposed, use dish washing detergent to bath or shower.

In my whole 40 years on this planet i have never got a rash from poison ivy. With that said my kids but one and my brother are highly allergic to it. Like have to go to er sensitive. I have rolled in and walked in it barefoot and so on and nadda. Hopefully i never get sensitive to it. I imagine i would have limits somewhere but i dont eat it or burn it so we wont find out there. Its always been kinda weird.