First post

and... why are there so many acorns this year?

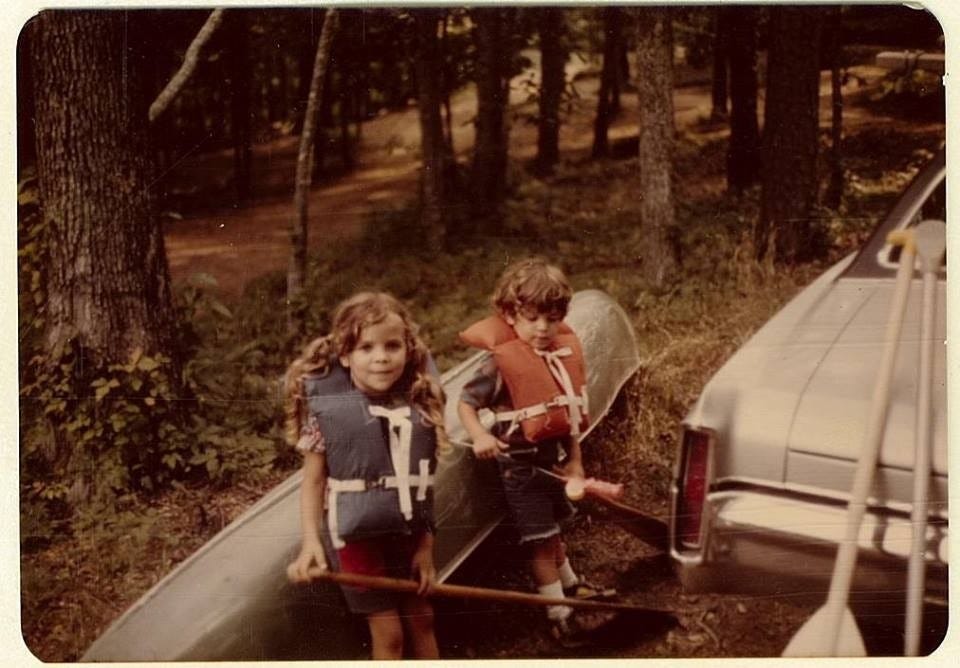

I grew up in the mountains of western North Carolina at a rafting company situated right on the Appalachian Trail. We lived deep in the bottom of the Nantahala Gorge, where there was no television reception but plenty of things to do outside, and since it was the 70s and 80s, I was free to roam the woods, rivers and creeks with my brother under very little supervision. I was naturally curious about everything I saw, and there were plenty of things to see in the Smokies.

Flash forward to today, and I am an avid hiker and mountain biker, so I spend a good deal of time in the woods. I like to notice things that others might miss – an oddly shaped tree, the way rocks are cradled amongst roots, the ghostly impressions of leaves rotting on a gravel road. I also have questions about some of the things I see – why are there foamy bubbles in this creek? Why does this tree have large bumps all over it? Do trees migrate? What made this leaf so lacy? I’m not a trained naturalist, but I was an elementary teacher, which means I’m used to being asked off-the-wall questions and researching the answer. This newsletter is a chance for me to share some of the interesting things I see along with the answers to questions I find myself asking.

So, without further ado, here’s the first “Natural Wonder” I found myself asking the other day:

Why are there so many acorns this year?

Some years, and this is one of them, I find myself tripping and sliding on piles of acorns underfoot on my favorite trails. They can act like collections of ball bearings, and make for interesting negotiations of corners and cliff-edges. The old-timers called these “mast years,” since “mast” is the botanical term for the fruit and nuts that fall to the forest floor as food for grazing animals. During mast years, oaks can produce 20 times their normal amount of acorns.

Having plenty of acorns must be nice for the squirrels and the deer, but why so many? Why would the forest suddenly provide what seems like way too many seeds for animals to eat, especially compared to years past?

It’s actually part of Nature’s amazing design. In many non-mast years acorns still fall from the mother tree, just not so prolifically. This means that the squirrels and deer (and rabbits, raccoons, foxes, and wild hogs) snatch all of them up for food and there are none left for what the tree’s original intention was – to produce a baby tree. These so-called “normal” acorn years, therefore, don’t usually result in much of a chance for a tree to produce a viable sapling to eventually replace it.

So, nature compensates by unpredictably flooding the market. Every few years the trees agree to produce a bumper crop of acorns that outnumbers the animals determined to eat them, thus guaranteeing some acorns will be leftover to take root and grow. It’s an unpredictable cycle because it also helps control the animal populations as well – if the oaks produced a consistent crop, the deer would simply adjust their populations to match, and the oaks would be back to square one.

Statistically speaking, each adult tree produces one replacement tree in its lifetime. Even though a mature tree will produce thousands of seeds, most of these are eaten by animals and some simply rot in the ground. Of the seeds that do take root, many of the resulting saplings are eaten by animals or die before maturity from drought or illness. Peter Wohlleben, author of The Hidden Life of Trees, says of a beech tree: “Assuming it grows to be 400 years old, it can fruit at least sixty times and produce a total of about 1.8 million beechnuts. From these, exactly one will develop into a full-grown tree.”

Mast years are a survival strategy for trees, an elegant design solution in what first appears to be a chaotic, random system.

Nature is pretty amazing.

Resources:

The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wohlleben

Detritus

(aka: random bits of somewhat related information)

Cool sculptures made of acorns

The largest acorn in the world is from a tree that lives in Mexico.

The largest (non-edible) acorn in the world is in Raleigh, NC

Eggcorns are a fun linguistic trick - basically, they’re “faulty phrases that still make sense” like saying someone has the “upmost” intelligence or that noise is “nerve wrecking”

Acorn cartoon

8 things you didn’t know about acorns

A beautiful time-lapse video of an acorn becoming an oak tree.

This is my first post, and I’d love to know what you think! Whether you have suggested changes, questions I might try to research, topics to look at, or parts you liked, please…

I love the picture your dad took, seems like yesterday 💜

Love this! Helps the inquiring mind. 😁 can’t wait for the next post