Does the appearance of a plant hint at its medicinal uses?

Plus a game -- try your hand at the Doctrine of Signatures!

I grew up in the Appalachian Mountains of western North Carolina around plenty of people who used wild plants as medicine. Many of them trusted God’s medicine more than the store-bought kind. Roy Dills was an old-timer who had a root cellar dug into the clay bank next to his house, and lining its dark walls were rows and rows of jars containing every plant imaginable.

Even though we had moved to the mountains from elsewhere, and were therefore “ferriners,” Roy got a kick out of sharing the wealth of the forest with us hippies. He’d caution that poke salit (salad) could only be eaten after the third boiling, morel mushrooms were best found under sycamore trees in early spring, and if you were going to eat ramps (wild garlic), you’d better not be the only one eating them or else you’d be sleeping alone.

Fast forward to present day, and a friend of mine recently asked if I’ve heard of the Doctrine of Signatures for medicinal wild plants. I had not.

I checked it out, even finding a description of it in my Peterson’s Field Guide to Medicinal Plants, and found that this Doctrine describes the idea that the outward appearance of a plant communicates how it’s helpful to humans. It’s an idea ancient healers used to note the usage of many wild plants. For instance, maidenhair fern can be consumed or steeped and poured over the head to treat hair ailments:

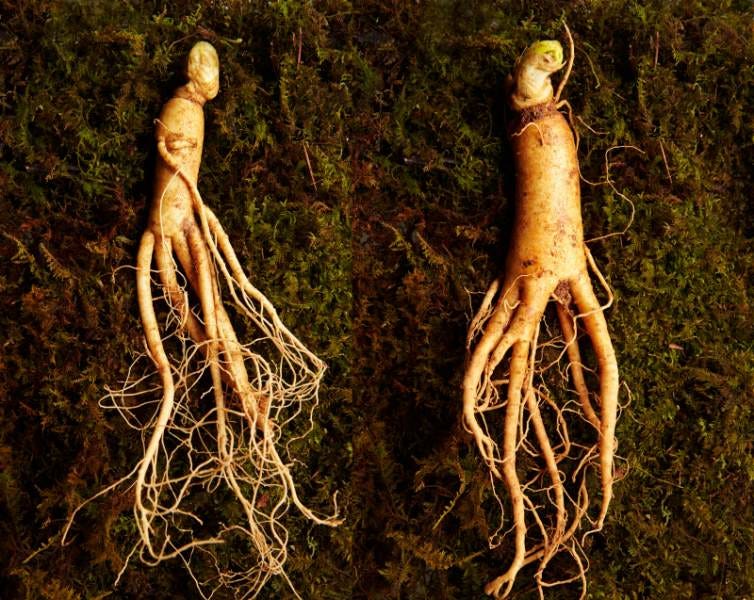

Or the idea that ginseng, with roots that look like a person, are so valuable for whole-body illnesses they can fetch $50 per pound (and are now endangered in the wild from over-harvesting):

Sometimes the Doctrine states that the plant might look like the disease it’s able to cure – like Lungwort, which has spots on its leaves like a diseased lung:

Can any of this be believed?

Does the appearance of a plant hint at its uses?

The Doctrine of Signatures is an ancient concept that appeared in early writing by Jacob Bohme, who wrote The Signature of All Things in 1621. Bohme and others believed that God marked plants with a sign or “signature” correlating to their purpose. In a world in which it was believed that the sun revolved around the Earth, the human-centric idea that God would visibly design plants for man’s specific ailments made perfect sense.

The only problem? As you’d expect, this simple interpretation of plant appearances is not always true. The Doctrine of Signatures is considered pseudoscience and, in some cases, has led to illness and even death. As one example, birthwort was used during childbirth due to its resemblance to a uterus, but it turns out to be carcinogenic and can damage the kidneys:

However, as Roy would say, even a blind squirrel finds a nut every once in a while, and it turns out that occasionally the appearance of a plant does correlate to its benefits. Walnuts, those omega-3 rich nuts that protect the brain from oxidative stress, do actually look like tiny brains:

Eyebright, with its bright-eyed flowers, is actually good for improving eyesight because it contains flavonoids which have antihistamine properties to help with hay fever:

Even before Jacob Bohme’s Doctrine attributed a divine intent to plant design, the ancient Greeks and Romans made connections between herbal remedies and plants’ visual appearances. One school of thought flips the Doctrine on its head by arguing these “signs” are simply mnemonic devices to aid the memories of ancient healers, many of whom were illiterate. The worm-like stems of purslane were a reminder to the Cherokee that the plant is good for wormy stomachs, and it has indeed been proven to treat intestinal parasites:

And perhaps the fact that willow trees grow in damp, wet places was simply a reminder to healers that rheumatism, often prompted by such dampness, could be treated with the bark of a willow tree. Years later, willow bark was discovered to contain salicylic acid, the basis for modern-day aspirin.

Many of the medicines we use today actually originated from native plants. Along with aspirin, morphine came from opium poppy and quinine was extracted from Peruvian bark. “A full 40 percent of the drugs behind the pharmacist’s counter in the Western world are derived from plants that people have used for centuries, including the top 20 bestselling prescription drugs in the United States today,” states the U.S. Forest Service. Of course, most of the time plants do not outwardly indicate their uses – a lot of trial-and-error had to happen to discover the use of wild plants and how to prepare them. But it’s fun to think about the visual connection between plants and their uses.

Game Time!

So now it’s your turn! Try your hand at identifying the medicinal properties of these plants from my Peterson Guide (answers at the bottom of the newsletter – no peeking!)

Weird Nature:

Game Show Answers:

What is BLOODROOT good for? Answer: B — it’s actually poisonous. The Cherokee used it for staining baskets. It was used in toothpaste and mouthwashes from the 1990s-2000s as a plaque-inhibitor, but was discontinued after it caused precancerous oral lesions…

What is LADYSLIPPER good for? Answer: B — it was widely used in the 19th century for “female” diseases such as nervous headaches, hysteria, and insomnia.

What is RATTLESNAKE PLANTAIN good for? Answer: A — this is a case of the Doctrine of Signatures actually being accurate. The leaves look vaguely like a rattlesnake’s skin AND the Potawatomi used it as a rattlesnake bite remedy by chewing the leaves and swallowing the juices.

I loved this exploration. Thank you for sharing--the game was super fun!

just recently one day looking at the mistletoes in the leafless wintertrees they made me think of tors/cancer-et voila: mistletoe extraxt is actually discussed and studied or already used(the results from a quick first google search were a bit conflicting in that regard)in cancer therapy.that s what actually brought me,bc i was a bit stunned, not actually expecting a match when looking up a possible connection between mistletoes and cancer,though i came across the overall concept of a connection between effect and appearance of plants before