Can snakes “choose” to inject you with venom?

or Why does it seem like I'm suddenly a snake magnet?

Welcome to Natural Wonders, where I research questions I’ve been wondering about in the outdoors. School is out (here in the south), the lake is hopping, and people are out and about in the woods — time to talk about our favorite slithery critters with fangs!

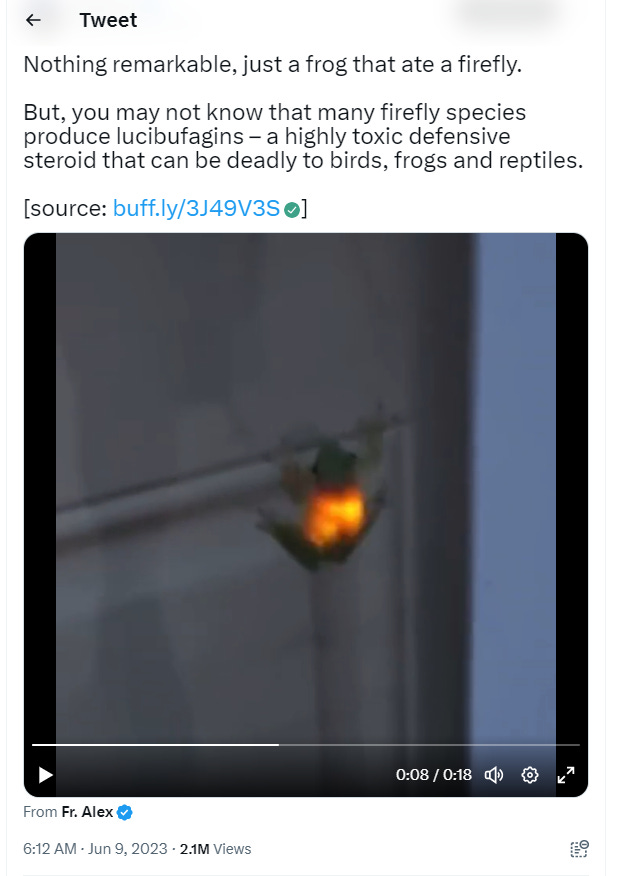

Toby got bitten in the face by a copperhead.

It was actually the culmination of what ended up being Snake Week at our house. At the beginning of the week, a member of our hiking club stepped on a small copperhead during our hike but was able to quickly flick it up into a rhododendron with his hiking stick. Toby and I were a short way behind but out of danger.

Two days later, while camping at Big South Fork in Tennessee, Andrew and Toby stepped all over a copperhead in some leaves in our campsite. Fortunately, it was morning in the upper 40s and probably cold enough to make the snake sluggish, though it did rear up in striking position and rattled its tail to warn them off.

An hour later we found a dead copperhead squished in the road in front of our campsite, and an hour after THAT we encountered one while riding our bikes (without Toby):

At this point we’d seen three copperheads in three hours and EVERY little root and stick looked like a snake. I was starting to wonder – was it a bad year for copperheads? Does the population ebb and flow like deer do?

We made it through the last few days of our vacation in the wilds of Tennessee without seeing another copperhead, but once we arrived back home that’s when disaster – in the form of a copperhead – struck.

That evening, Toby went to his favorite pile of leaves to pee and – from his perspective – lightning struck him in the face. He yelped and pawed at his face, Andrew yelled for me to call the emergency vet, and in general all H%*LL broke loose.

Suddenly, we had a truckload of questions about venomous snakes.

Can copperhead bites kill a dog? Should we carry him to keep him from walking or does that matter? Will the vet give him antivenom and if so, what is that and how does it work? This snake was the biggest copperhead we’d ever seen – do bigger snakes pack more venom? Toby’s face was obviously swelling, so he’d definitely been injected with venom – can snakes control how much venom they inject? Could a snake choose not to inject any venom at all? What if this had been a rattlesnake bite? How do we prevent this in the future? What happens if he gets bitten again?

The lowdown on venomous snakes:

Here in the United States, we have just four types of venomous snakes: rattlesnakes, copperheads, cottonmouths, and coral snakes. In my particular neck of the woods, northern Georgia, we only have copperheads, timber rattlesnakes, and pygmy rattlesnakes. People claim to have seen cottonmouths this far north, but they’re usually actually water snakes that, while aggressive, are not venomous. Last week we saw a reddish water snake similar to the one below, but notice that the copperhead has marks like Hershey Kisses while the water snake has simple bands:

Hershey kiss-shaped markings are the dead giveaway for identifying copperheads.

I’ve also heard that venomous snakes have elliptical pupils like cat’s eyes while non-venomous snakes have round pupils. You can see that in the pictures above.

Of course, the main problem with that is once you know the shape of a snake’s pupils, you’d better hope they’re round. The other problem: while pit vipers do have elliptical pupils, so do some other harmless snakes. And some venomous snakes have round pupils. Making it even more hopeless, in low lighting elliptical pupils will expand so that they look almost round. So, no need to go get a close-up view of Mr. No-shoulders. Just look for Hershey Kisses or a rattle on the end of the tail.

Two days ago, after I’d written most of this issue about venomous snakes, some friends and I fortuitously came across a rattlesnake while biking. I will testify that not a single one of us was looking at its pupils. The snake went from stretched out to coiled up very quickly, and began its high-pitched rattle to warn us off. It was the first time I’ve ever heard a rattlesnake in the wild, and it was pretty amazing. We gave it a wide berth, since they can strike a distance two-thirds their body length, and this one was about 3 feet long:

Each year, about 7,000-8,000 people are bitten by venomous snakes in the United States. However, only around 5 people die from those bites. That number is extremely low because most people are able to access medical help in time. Even in Australia, which has around 100 venomous snakes including the death adder, tiger snakes, and sea snakes, only a handful of people die each year. The story is not the same in less-developed parts of the world with less access to medical intervention. In India, for instance, 10,000 to 50,000 people die per year from snake bites.

For most of us, the bigger problem with snake bites isn’t death but rather the long-term injuries or effects from the bites, including losing the use of a limb or digit. The majority of people get bitten on the leg as they accidentally step on a snake (like Andrew and Toby did in Tennessee) but a smaller number of people get bitten on the hand or arm, and that’s when doctors know testosterone and alcohol is likely involved.

Dogs tend to get bitten on the face as they attempt to smell the snake, while cats get bitten on the paws because they bat the snake with their claws. Like people, most pets don’t die from copperhead bites; however, if they get bitten on the tongue it’s like a direct injection of venom and is very often fatal.

The best bet, as our vet told us, is to give the animal a dose of antivenom to neutralize the venom, stop tissue damage, and most importantly stop the pain. Copperhead venom can remain active within tissue up to 72 hours after the bite. This is why antivenom is so important – it neutralizes the venom and prevents necrosis and loss of limbs that can follow from untreated bites.

Antivenom is produced by injecting horses and sometimes sheep with the target venom, causing the animal to create antibodies which are then harvested from blood draws. Each antivenom is specific to the type of snakebite – in other words, you need a positive identification of the snake so the doctor knows which type to give you. We brought in a picture of the snake that bit Toby, but our vet told us he once had a woman bring in the actual copperhead snake, still alive, in a plastic Walmart shopping bag.

Don’t do that.

Occasionally, a person or animal will get a “dry bite” from a venomous snake. Our vet was skeptical of the idea, saying that what people think are dry bites are simply cases where the snake struck and missed. However, my research shows snakes can definitely bite and inject very little, if any, venom. Snakes don’t bite because they see humans or dogs as prey. Rather, the bites always occur because the snake feels threatened. In these cases, snakes may benefit from engaging in “dry bites” where they don’t inject venom since it takes time and energy to produce its own venom, sometimes up to 60 days to replenish a full gland of venom. These bites serve as warnings without depleting its supply.

This study found that rattlesnakes are able to inject more venom into larger prey and lesser amounts into smaller animals. This takes practice, however, and juvenile snakes weren’t always able to exhibit this type of control. Interestingly, however, snakes that are hungry tend to inject less venom than well-fed snakes do – perhaps because they are conserving their venom for future strikes.

Dry bites can also occur due to something the human did – for instance, wearing denim has been shown to reduce the amount of venom injected by 66%. There also appear to be some cases in places like the Amazon rainforest where people have developed immunity by being repeatedly bitten and developing their own antibodies, thought this hasn’t been carefully studied.

Then there’s this guy, who intentionally injected himself with venom from multiple snakes and claimed it gave him immunity. He’s in amazing shape in this video, and lived to be 100, so maybe he’s onto something. But he is missing some digits:

So, what should you do?

What should you do if you or a loved one/pet gets bitten by a venomous snake? The list of what NOT to do is a pretty long one. DO NOT:

use a tourniquet to cut off blood flow

suck out the venom

slice open the wound even further

ice down the wound (you can freeze/damage the tissue)

(do not) wait to see if it’s a dry bite or not – snakes have lots of bacteria in their mouths and there will almost always be swelling and infection either way

cut open a chicken and apply the fresh entrails to the wound (seriously – this, along with holding a bottle of turpentine on the bite, was apparently a home remedy)

Instead, the best thing to do is:

stay calm – keep the heart rate low and carry the person/animal if possible

remove rings, watches, collars – anything that could be constricting once swelling starts

mark the leading edge of swelling with a permanent marker and repeat every 15 minutes, writing the time alongside

take a photo of the snake – the doctor/vet will want to know which antivenom to give.

get to help as soon as possible. The sooner you can get antivenom, the better.

People who are bitten by copperheads oftentimes don’t get antivenom but instead are simply observed for adverse reactions beyond simple swelling. A big reason for this is cost – antivenom dosages can cost between $44,000 and $115,000 for humans. It’s a much smaller cost for pets – Toby’s antivenom cost around $700 plus other expenses.

Rattlesnake bites, on the other hand, oftentimes do require antivenom because their venom is 50 times more potent than a copperheads’. Thanks to reader Burt (who took the rattlesnake video above) for reminding me that I wrote in an earlier post:

Opossums are immune to rattlesnake venom because “a protein in their blood binds to the toxins and neutralizes them.” Scientists have found that isolating this protein and combining it with the venom before injecting it into mice makes the venom ineffective. This special opossum protein is being studied by scientists as a possible alternative to antivenom, which is very expensive to produce.

Several friends I’ve talked to have said to give Benadryl in the case of a snake bite, however this is not a good treatment. Benadryl is an antihistamine that treats allergic reactions. The swelling from a snake bite is not a reaction but is due to its hemotoxic venom, which means it affects the blood (hemo = blood) and cardiovascular system. The venom attacks the red blood cells and can either cause massive clotting or the inability to clot, both of which are extremely damaging. Our vet suggested the only time Benadryl might be helpful is if Toby got bitten a second or third time in the future and develops an allergy to snake venom.

Let’s hope that’s not the case.

You know where it is NOT fun to find a snake? At the head of your air mattress when you are camping. Fairly certain it slept with us at least one night if not more. It was cozy as could be! Gave me the heebee jeebees though! Good thing we were packing up to head home anyway when we found it.

Oh no, I'm so glad Toby is okay.

I'm grateful there are no venomous snakes in New Zealand. Actually, there are no snakes at all, but I'm ambivalent about that point. I'd be delighted if we had native, non-venomous snakes, but I'd be upset if non-native snakes established here.

Thanks for another cool article.