Welcome to Natural Wonders, where I hope to pique your interest each week by sharing some fascinating questions and answers about natural phenomena. If you’re new here or if someone forwarded you this email, you can subscribe below.

Check out past posts by going here and see who I am and what Natural Wonders is about here.

Last week when I was walking with Oscar on our property, I heard the rattle of a pileated woodpecker echo from the hillside above me. It was loud and extremely fast – I couldn’t have counted the number of “knocks” per second if I’d tried. It sounded something like this:

I suppose the tree must have been hollow, to have it echo so far across the forest, and though I couldn’t see him clearly, I imagined his head pounding on the tree faster than I could even tap my fingers against my leg. (Try it! It’s not easy!)

I know woodpeckers eat insects and grubs in trees, but they also use their beaks to carve out holes to build a nest like this tough cookie, who’s basically using his head as a hammer:

That looks extremely painful! Their neck muscles must be really strong, and what about their skulls? It made me wonder…

Why don’t woodpeckers have brain damage?

I have more than a little vested interest in this question because around 20 years ago I wrecked my bike in fairly spectacular fashion and ended up with a concussion. I lost consciousness and when I revived, I didn’t recognize my husband or anyone around me. At the hospital I kept asking the same questions over and over. When we stopped at the pharmacy on the way home, I wouldn’t let my husband back into the locked car because I didn’t know him. I was told these stories weeks later, since I had no memories of the accident or the hours afterwards. Later that summer, I wrote about having to relearn how to read and how it gave me insight into what struggling students experience.

The doctors explained that when I flew through the air and landed on my shoulder and head (breaking my helmet in the process), my brain had sloshed back and forth in my skull, bruising my prefrontal cortex. Fortunately, I didn’t bleed inside my brain, but I did experience vertigo because of loosening up important parts of my inner ear. I was extremely fortunate that my injuries were temporary, though it was over a year before I could reliably remember people’s names and recall words I needed in conversation.

If all of that happened to me from just one impact with the ground, how in the WORLD does a woodpecker prevent injury to its brain when it can strike a tree 20 times per second? The force woodpeckers experience as they strike trees is about 10 times the force that would cause a concussion in a human brain

There must be something special going on with a woodpecker’s skull.

It turns out there is. Inside a woodpecker’s skull is a special bone that wraps around their brain, holding it tightly in place like a seatbelt. It’s called a hyoid bone and it acts as a shock absorber, similar to a shock on a bicycle or motorcycle fork.

In the photo below, the bone on the bottom right (b) is the hyoid, and on the left you can see how it wraps around the skull. (The hyoid bone on the top right belongs to a hoopoe, not a woodpecker)

When I was at the local bike trail recently, talking with some friends about this cool fact, a guy nearby mentioned that he’d always heard that woodpecker’s tongues wrap around their brains to keep them in place. While woodpeckers do have tongues that are three times the length of their beaks (for reaching deep into holes for insects), their tongues don’t wrap actually around their skulls. That’s probably a misunderstanding that developed because the hyoid bone is attached to the muscles of the tongue.

When the woodpecker stretches its tongue forward, it tightens the hyoid bone against the skull. In the illustration below, drawing A is the hyoid bone with the tongue relaxed, and B is with the tongue stretched forward, tightening up the hyoid.

It’s basically an adjustable bike helmet for the woodpecker’s brain. Pretty ingenious design, don’t you think?

It pays to be a bird-brain

There are a few more design elements that help protect a woodpecker’s brain as it strikes a tree.

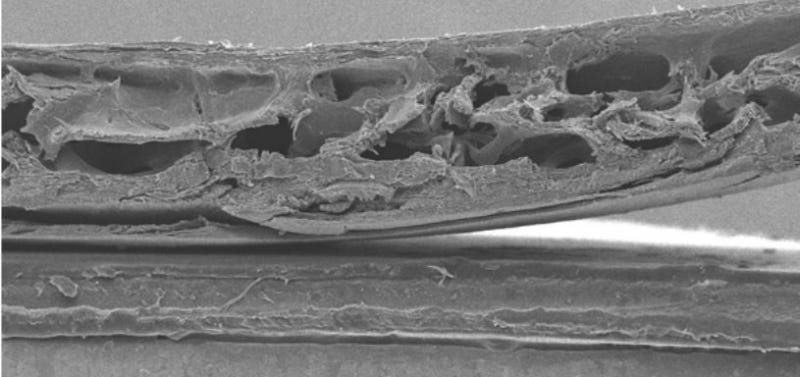

One factor is simply the fact that their brains are fairly small and are packed tightly into their skulls, diminishing the “sloshing” that could contribute to damage and concussions. Also, the woodpecker has spongy bones in its skull that help cushion the blows, similar to the Styrofoam in a bike helmet.

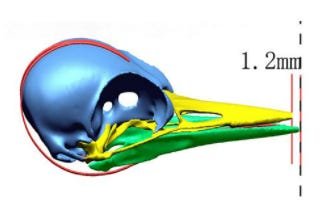

Another factor that helps the woodpeckers is that the bones in their beaks are not exactly even. As you can see below, the bottom beak bone, which is connected to the woodpecker’s neck and body, is just a tiny bit longer than the top beak bone, which is directly connected to the skull. This means the bottom bone gets the majority of the initial impact and transfers that force down through the body.

Finally, the way the woodpecker’s brain sits in its skull also helps – it’s situated so that a large area of the brain contacts the skull as it strikes a tree. This allows the energy to dissipate across a larger area rather than being concentrated, which is what happened when the smaller frontal lobe of my human brain bounced off the inside of my skull.

All of these fancy skull adaptations don’t protect woodpeckers all the time – they’re just as susceptible to major injury if they fly into a window, for instance. That’s the thing about adaptations – they’re effective, but also fairly specialized.

Prompt: On your next walk, listen for the echoes of a woodpecker. Many times they’re pecking for food, but when it’s loud and reverberates across the forest (like in the 1st video above) they are “drumming” to communicate with other woodpeckers. You might even be lucky enough to see one hacking away at soft wood to expand a hole for a nest.

What evidence have you seen of woodpeckers near you? Have you heard a pileated woodpecker “laugh”? Woody Woodpecker was modeled after this specific woodpecker, which does have a distinctive “laughing” call. Let us know what you’ve seen and join the conversation:

Weird Nature

Detritus

Something frightening is happening in the Arctic. My friend Melanie has written a fascinating and sobering explanation of what’s happening to the Northwest Passage and the rest of the Arctic. She’s titled it “Avalanche Warning” and the reason why is a gut-check.

Many lizards have detachable tails as a safety mechanism so they can escape a predator. But have you wondered how these detachable tails stay on in the first place?

I can’t decide whether this baby aardvark is adorable or creepy. Regardless, they picked the appropriate name for him.

This video is an engaging synopsis of everything I shared above about woodpecker’s brains, and has some amazing slo-mo video of a woodpecker striking wood at the 4:30 mark.

Thanks! A nice writeup!

This was absolutely fascinating, thank you.