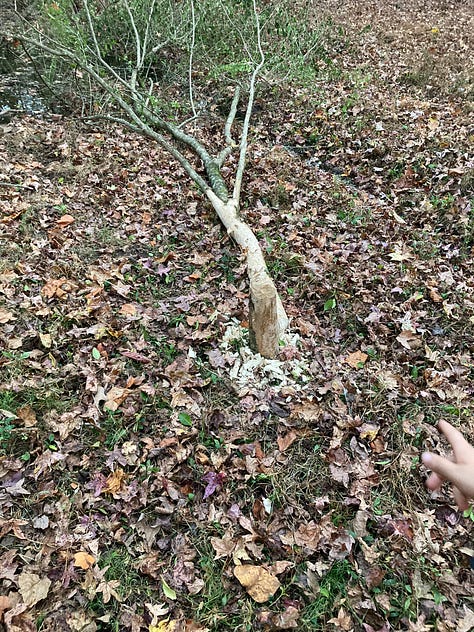

This week’s Natural Wonder comes from a reader, or actually, a group of readers. This sweet family with six outdoor-loving children found a series of beaver dams that form four small ponds near their home. They’ve also found lots of evidence of beavers peeling off tree bark and cutting trees in the area:

This cool discovery has the kids asking lots of questions: Do beavers eat the wood they chew? Do they hibernate? Are they related to groundhogs? What DO they like to eat? Can they climb trees?

Their questions made me curious myself. Why do beavers feel the need to build dams? They aren’t corralling fish because they’re not carnivores, right? Do they just want to protect themselves by surrounding their lodge with water? But some beaver ponds (including one downstream from our house) don’t have noticeable lodges – in those cases, where do the beavers live? For that matter, why did I see someone tearing down that beaver dam several years ago – are they considered harmful or a nuisance in some way?

A bevy of beaver questions!

The kids are right to wonder if groundhogs and beavers are related – they do look very similar:

They are both rodents, but mature beavers are much bigger than groundhogs – usually three to five times larger, getting up to 60 pounds in some cases. They both live underground, but beavers are semi-aquatic while groundhogs are not.

Beavers are the largest rodents in North America. Like all rodents, their incisors continue to grow throughout their lifetime, meaning they must gnaw constantly to keep them a manageable length, just like sign-chewing squirrels. Their incredibly strong teeth are usually a bright-orange color due to the iron in their enamel that helps strengthen the teeth and also makes them resistant to acids.

Why do beavers need such strong teeth? It has to do with their incredible ability to completely change their environment. Imagine you’re a deer who occasionally visits a peaceful stream trickling down a hillside with just a few purple asters and mountain laurel alongside the bank. If a beaver moved in, she could fell trees, gather branches, pack mud and create a watertight dam within 24 hours. Over time, you would notice the area around the pond begin to change – ducks and herons would arrive to build nests and raise their young while water-loving plants such as lilies and cattails would embed along the banks. The slowing of the stream water would mean an increase in water quality as silt settled and prevented erosion downstream. The building of the dam would also have an effect on the temperature of the water downstream – the water contained behind the dam would slowly seep through the mud to the water table below and emerge downstream 4.5 degrees F cooler than above the dam. It’s for these reasons and more that beavers are considered a keystone species – if they are removed, it has a drastic effect on the surrounding ecosystem.

The largest beaver dam in the world is in Alberta, Canada and is half a mile long. Beavers have been working on it since the 1970s, making a wetland large enough to be seen from space.

If you look closely in the photo above, you can see the beavers’ lodge in the middle of the pond. That lodge is the reason beavers work so hard – generation after generation in this case – to keep their dams watertight. It’s not to create a lush wetland for a massive number of plants and animals – they simply want to install a moat around their mud and stick pile of a home to prevent bear, coyote, and fox attacks.

The lodges always have an underwater entrance as a protective measure. If they aren’t able to create a traditional lodge, they will instead build tunnels in the bank of the pond but with underwater entrances. In other words, the creation of the pond is the sole reason for their survival. A slow waddling, almost-blind beaver on land becomes a sleek, streamlined missile as soon as it hits the water.

Beavers are made to be underwater. They can hold their breath up to 15 minutes, have a set of transparent eyelids that serve as goggles as they swim, and have two pairs of lips – one set is behind their teeth, which allows them to gnaw on sticks underwater.

Beavers mainly eat aquatic plants along with small branches and twigs of trees. They also will chew off the bark of larger trees in order to get at the juicy cambium layer underneath. But they don’t eat the dense heartwood of trees – when you see beaver-chewed trees gnawed deep into a stump, that’s because they’re using the wood for dam material.

Unless you’re lucky, you probably won’t witness much actual beaver activity. They tend to be nocturnal and crepuscular, meaning they’re primarily active during the twilight of dawn and evening.

During the winter, you’re even less likely to see them. They don’t hibernate, even up in the cold, snowy forests of Canada, but they do lower their body temperatures to conserve energy and spend most of their time in their lodge. To prepare for this less-active time, they store fat in their tails, which can expand to three times their normal size. They also drag tasty sticks and branches to the side of the pond or even store them in their dam for later eating, since winter trees with no sap make for much less appetizing snacks.

Finally, do beavers climb trees? Well, not really. They’re too bottom-heavy, with their chunky tails and large webbed back feet, to be nimble enough to make it up a tree. However, they can climb along horizontal trees or leaning trees that have fallen. If you see a “beaver” in a regular tree, however, it’s probably actually a groundhog.

But wait! There’s more!

One last fascinating fact: beavers produce a dark, thick liquid from a sac underneath their tail that’s used to mark their territory or to attract mates. It’s called castoreum. Somehow, humans discovered this molasses-like fluid is… delicious?

I’m not kidding.

Castoreum apparently smells like vanilla and is used today to flavor ice creams, candies, perfumes and sodas. Several companies, such as Tamworth Distilling, produce alcohol flavored with beaver castoreum. Their Eau du Musc is a whiskey “which has a bolstered mouthfeel with a vanillin nose and notes of spice.”

There you have it, folks. We must preserve our beaver population for their function as a keystone species and their contributions to vanilla-flavored foods everywhere. If you’re concerned about what’s in your leftover Halloween candy, however, you don’t need to worry too much -- with the advent of artificial vanilla flavoring, only around 300 pounds of castoreum is collected and used each year.

What a fascinating species, real ecological engineers. I can't think of anything in New Zealand which does anything on this scale.

Ah BeaverTails, an Ottawa Valley tradition. But as far as I know, they are named that way for the shape. Only a couple of flavors have vanilla which could be based on Castoreum I suppose but the website certainly doesn't highlight that. https://beavertails.com/products/ My favorite is the Killaloe Sunrise (cinnamon, sugar, lemon juice). Worth freezing your fingers for if you don't want to get your mitts sticky after a morning ski or a long skate on the Canal.