Why aren’t fruits and vegetables as nutritious as they used to be?

It's not because they're all deep-fried...

I’ve never been a gardener. Something about plants’ persistent need for care and my working/hiking/mountain biking schedule just doesn’t make for a prolific crop yield.

This year we decided to try container gardening, thinking that would be easier and while it certainly keeps down on the need to weed, the plants still require regular watering and better soil than the mulchy “container soil” bag we bought at the local big box store.

Still, we have had the occasional cherry tomato, and a few (read: one) pepper before caterpillars ate the plants down to nubs. Fortunately, my friend Beth gave me some heirloom tomatoes so I could make some delicious summer ‘mater sandwiches.

It had me thinking, though: everyone says homegrown vegetables (especially tomatoes) taste so much better than store-bought. Then I saw a headline stating it’s not just the taste of grocery store vegetables that has declined – their nutritional value is not as good as it used to be. Why is that? Is there anything we can do about it? Are the pitiful little vegetables I’ve managed to grow this summer not even worth the effort?

Why aren’t fruits and vegetables as nutritious as they used to be?

First of all, it IS true that the plant foods we buy in the grocery store, even the organic ones, are less nutritious than what our grandparents used to eat. A landmark study in 2004 compared the nutritional value of fruits and vegetables from 1950 to 1999 and found a decrease in micronutrients such as protein, calcium, iron, and riboflavin. Another study found that protein in wheat has decreased 23% since 1955 along with decreases in iron, magnesium and zinc. One study even stated you would have to eat eight oranges today to get the same nutritional benefits as your grandparents would have gotten with one.

This is incredibly depressing.

Of course, it doesn’t mean we should skip the fruits and vegetables and only eat processed foods – there are still plenty of nutrients left in the fresh produce section of the store. But it does mean we’re not getting the best bang for our buck out of what we eat – scientists are concerned this decrease in nutrients could eventually result in more difficulty fighting off chronic diseases.

And, too, these less-nourishing vegetables affect more than just us – domesticated animals such as cows, pigs, and chickens also rely on mass-produced plants. When they eat food with less nutrients, we end up with less nutritious meat.

Why is this happening?

Modern agricultural processes are to blame. Large farms are paid for their products by the pound, so they aim for the highest yield possible from each acre of land. They plant single crops that are easy to harvest, over-use fertilizers that boost production but kill soil nutrients, and breed for pest-resistant, overly-large varieties of their crop.

All of this puts much more stress on the soil and results in the existing nutrients being diluted across much larger crops than we had 70 years ago.

In healthy soil, whether in a field or a forest, plants rely on a network of underground fungi for nutrients. These mycorrhizal fungi form a symbiotic relationship with plants, supplying them nutrients from the soil in exchange for sugar and carbohydrates that keep the fungi going. In a forest, this network of underground fungi connects trees to each other, allowing them to exchange nutrients with each other and even communicate dangers, such as insect invasions.

These fungi also attack plant pathogens and filter out heavy metals from the soil, preventing them from reaching the trees and resulting in concentrations in some mushrooms. “No wonder radioactive cesium, which was found in soil even before the nuclear reactor disaster in Chernobyl in 1986, is mostly found in mushrooms” (The Hidden Life of Trees, p. 52).

Fungal networks take time to establish, however, and if soil is repeatedly tilled then these symbiotic relationships are not allowed to form.

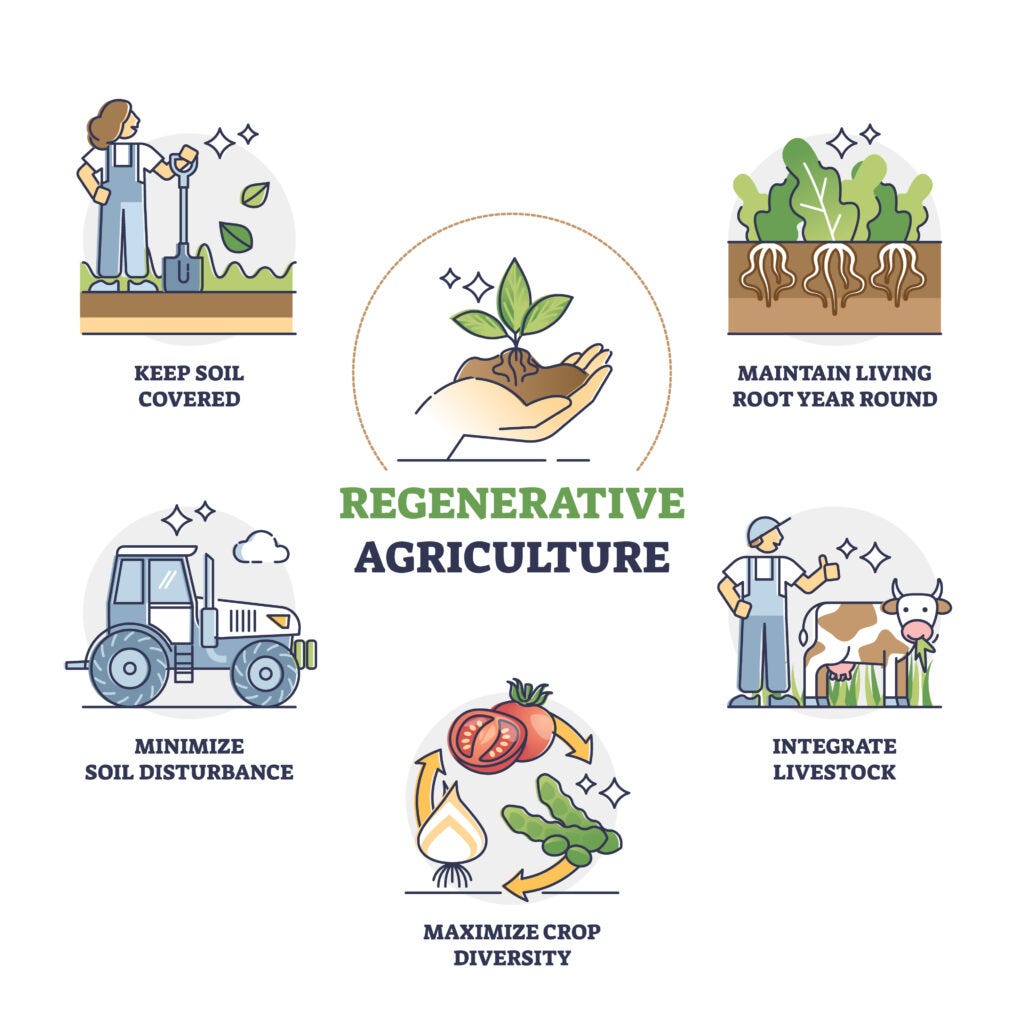

There is a solution, however: regenerative farming. Regenerative farms use sustainable methods that preserve and naturally enhance soil health. This includes not tilling fields, adding compost, rotating crops and using goats to keep down weeds rather than mowing.

Regenerative farms are not the same as organic farms. To be considered organic, a farm cannot use synthetic fertilizers or pesticides. But they are allowed to repeatedly till large fields, plant monocrops, and mass-produce high yields of their target food.

This short (4-minute) video does a great job of explaining how regenerative farming works:

Food from regenerative farms is more nutritious than even organic farms that use traditional gardening methods: “Researchers studied cabbage, carrots, spinach, and soil from Singing Frogs Farm and discovered that the cabbage grown on the regenerative farm had 46 percent more vitamin K, 31 percent more vitamin E, 33 percent more vitamin B1, 60 percent more vitamin B3, and 23 percent more vitamin B5 than cabbage from the regularly tilled organic field. The cabbage also had more calcium, more potassium, more carotenoids, and more phytosterols.”

You can find foods that have been produced by regenerative farms by looking for labels like these (click the picture to access the webpage or click here):

You can also find more nutritious, more delicious fruits and vegetables by heading to your local farmer’s market. Meeting the farmer gives you a chance to ask them about how they produce their food and supports small farmers at the same time.

Or you can make friends with a neighbor who has a garden and offer to exchange or pay for food when the garden is prolific. I know plenty of folks who can’t give away zucchini fast enough when it’s in season. My mom used to threaten to leave bags of vegetables on people’s doorsteps in the dead of night just to get rid of squash.

Of course, that’s not me. Our pitiful garden went nowhere this year. Now that I’ve done this research, I’m pretty sure that (along with my lack of care) our poor soil was to blame for much of it. Next year I’ll plan on heading into the forest to dig up topsoil rich in nutrients and fungi to fill my containers. Hopefully I’ll be sneaking food onto porches by summer’s end…

Armadillo Update

We continue to have no yellow jacket nests in our yard with some evidence of armadillos having dug up several nests. But Florida is beginning to have a leprosy outbreak and armadillos are mentioned as a possible source (click to view):

Weird Nature:

(click to see video)

This subject deserves careful discussion because I have heard similar narratives multiple times. I am going to sound a bit cranky, but I find this approach to food (aka Nutritionism) less than satisfying. “Nutritionism” considers particular foods as mere vehicles for “nutrients”, and is a piecemeal rather than holistic view of why we eat what we eat. To a greater or lesser degree, it plays fast and loose with science in the service of what amounts to an ideology (or belief system). We eat to stay alive and grow, eating many classes of materials in varying amounts. In human diets through most of evolutionary time, some essential compounds have been needed only in very small amounts and have been so reliably present in our food that our bodies have lost the ability to synthesize them, instead getting them from our food. We call these vitamins, and above a certain minimum, getting more of them does not improve our health. Therefore, in the context of this essay, the relevant question is, do the fruits and veggies of Big Ag, when part of a reasonable diet, lead to vitamin or mineral deficiencies? I would also add that many of our foods are fortified with vitamins and minerals, so a second question would be, does it matter where the vitamins (or minerals) come from? In other words, is a vitamin from a tomato different from the same vitamin in a pill? I think these are topics worth consideration.

I was curious about the data behind this essay, so I read the references and looked at the data. From my reading of these sources, I am skeptical about the subsequent interpretation in the articles that followed. Indeed, even the authors of the original articles seem skeptical. For example, in the article about iron in Australian veggies, the abstract states, “The majority of vegetables had similar iron content between two or more timepoints. … no definitive conclusions could be established.” In the British wheat study, after 1950 both the yield and grain size approximately doubled over pre-1950 values, largely because the starch content increased. Therefore, protein and mineral concentrations (not necessarily amounts) decreased as the grain size and yield increased. For the USDA study of 43 veggies between 1999-1950: the abstract reports decline for 6 nutrients but no decline for 7 others, and states, “We suggest that any real declines are generally most easily explained by changes in cultivated varieties between 1950 and 1999, in which there may be trade-offs between yield and nutrient content.” The derivative articles do not mention the skepticism expressed in the original research articles, nor the possible complexities of meaningful interpretation.

I have gardened in the past and loved it. I also understand that the scale and methods of big agriculture are off-putting in many ways. But it seems to me that the success of Big Ag has been to bring production up and prices down. I doubt that the family farm, as pleasing as it seems, can replace that for most Americans.

Call me a curmudgeon if you must, but why add “nutrient anxiety” to an activity that can be about pleasure and life in full. In describing a reasonable diet, Michael Pollan said it well: eat a variety of foods, eat moderately, and eat largely plants. I say, do that and you won’t have to give much thought to how much of vitamin x is in food y.

I wish you better gardening success next year!

Because we have lost our connection to the land. The food has become disassociated by planes, trains and trucks. Ask a kid in an urban setting where food comes from- their answer will shock you - McDonald’s