Do me a favor and go outside for a quick break. Take a look at your car’s windshield. Notice anything odd?

If you’ve been driving for more than 20 years, you might notice that your windshield is, well, too clean. When’s the last time you used that squeegee thing at the gas station while your tank was filling up? Growing up, I remember being fascinated by the transformation as my dad rhythmically cleaned first one side and then the other of all the bug guts and bits we’d picked up on our drive.

But nowadays, my windshield stays fairly clean and I can’t remember the last time I cleaned it.

Why is this?

Are insects going extinct?

According to scientists, there has been a noticeable decline in the world’s insect population since around the year 2000. One way we know this? The windshield test. Researchers in Denmark have been studying bug spatter on windshields since 1997 and found an 80% decrease between 1997 and 2017. Another study in the U.K. asked drivers to add sticky film to their license plates and found a 50% reduction in insects captured between 2004 and 2019.

Admittedly, these studies only capture data on flying insects that appear at car-height in particular areas of Europe. So, some folks, like entomologist John Acorn, doubt this decline and argue the data is too limited – by season, time of day and micro-environments along roadsides. He says, “Humans are notoriously bad at detecting trends, and we generally remember things according to the ‘peak-end rule,’ in which we recall the peak of an event (e. g., the messiest windshield of summer) and the end (e.g., the last windshield of the season).”

Even though the Windshield Phenomenon makes sense to us laypeople, maybe it isn’t the best way to collect data. But we can’t deny that insect populations are on the decline.

Quite a number of studies suggest that overall, there are fewer insects than there used to be, particularly flying insects such as bees, butterflies, moths, beetles and dragonflies. Germany has found over a 5% reduction in flying insects each year, adding up to a 75% decrease in the past 25+ years. Not all species are declining, however – some invasive species are increasing, like the Joro spiders in my backyard.

Our planet hosts 1.1 million different species of insects – or at least, that’s how many we’ve identified so far. They represent about 80% of all animal species -- including humans. In other words, humans, plus all other living organisms including birds, deer, rats and fish, only represent 20% of living species on earth. The rest are insects. In fact, the 20 quadrillion ants on our planet outnumber humans by 2.5 million times. There are literally tons of insects on our planet.

So, is it really that bad if we lose a few? Aren’t they just pesky, biting pests that eat our crops and disturb our picnics?

Actually, our planet wouldn’t be able to survive without them. Three-quarters of our crops depend on pollinators to grow the strawberries, almonds, squashes and apples we eat. We already know that honeybees, our main friendly pollinators, are becoming more and more scarce. Farmers now hire traveling beekeepers to pollinate their crops since they can’t rely on local populations to do the job.

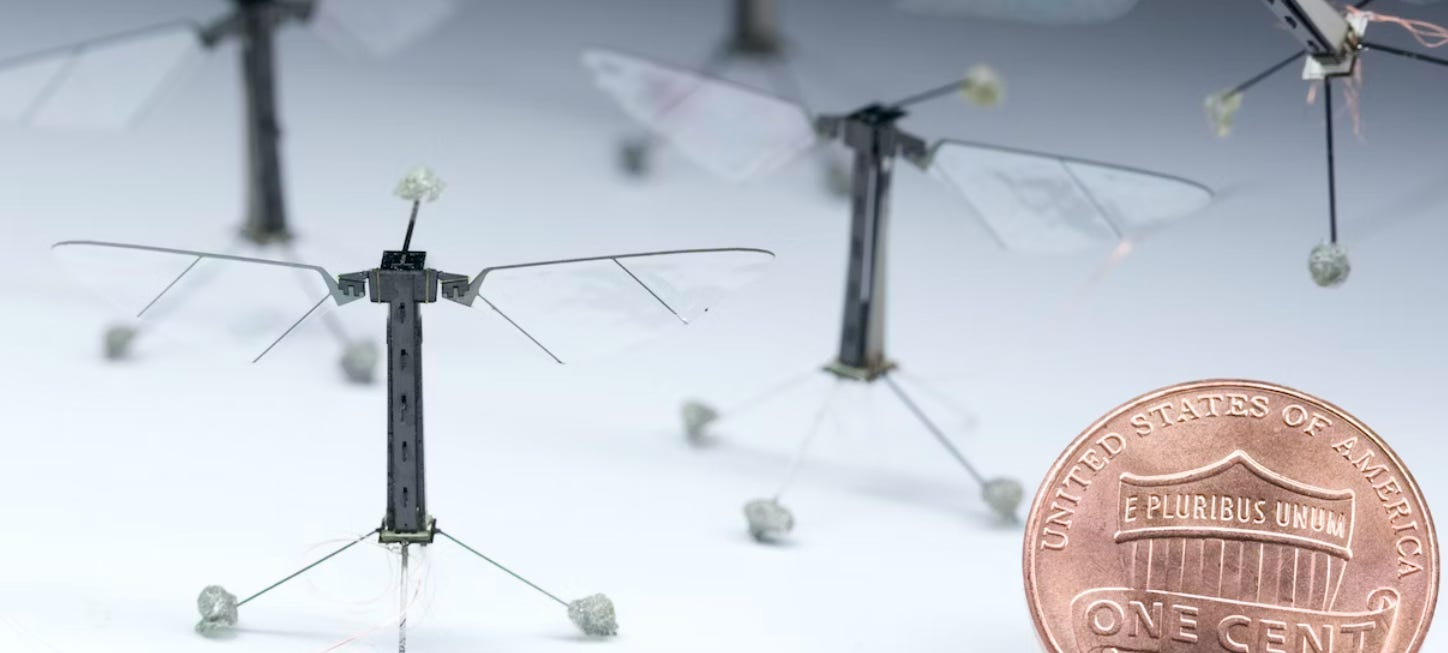

As if that’s not enough of a sign that we’re in trouble insect-wise, scientists are now developing robotic bees about half the size of a paperclip that are capable of pollinating crops (and also surveillance, but that’s a topic for a different newsletter).

OK, so if these robotic bees can take over the job of the pollinators then we don’t have to be as worried about the recent insect decline, right? Well, only if you don’t mind the accumulation of dead animals and feces everywhere you step. Insects are major recyclers – after vultures have finished eating a carcass then flies, ants, and beetles cart off the rest of the miniscule parts. The same goes for all the animal dung scattered throughout the forest (and your yard). Not to mention dead trees – termites do us a favor by eating away old logs and returning those nutrients to the soil.

Insects are also a key part of the food chain and serve as the main source of food for animals like swallows and swifts, bats and bass, carp and chameleons. Finally, insects such as ants support our ecosystems by dispersing seeds, as I learned about in this great issue of Walter’s Newsletter.

Hopefully we’ve agreed we can’t do without insects – our planet would most likely collapse without them. So, what’s causing the decline? And what can we do about it?

I thought the biggest problem would be pesticides, or maybe global warming, and while those do contribute, the biggest factor contributing to insect decline is the ways humans have altered the land. We have eradicated 70% of grasslands and 87% of wetlands in developed countries, and left pockets of forests isolated from each other. In their place we build malls and shopping centers, subdivisions with manicured lawns, and massive farms with acres of tilled soil. Insects are losing their natural habitats and the plants and undisturbed soil they need to survive.

Here in Georgia, our Department of Transportation evidently thinks it’s easier to spray a defoliator along the roadside than it is to trim the trees, but this a) looks incredibly ugly and b) kills off any plants that might have supported insect life:

Insecticides obviously harm insect populations. Many are broad-spectrum poisons that kill a range of insects other than the target – if you dust your tomatoes with Sevin dust to prevent caterpillars, you’ll likely also infect and kill any honeybees that attempt to pollinate the flowers. Instead, try using natural pesticides or try planting marigolds, chrysanthemums, or other plants nearby to deter insects. When I was growing up, we always planted marigolds along the edge of our garden to deter insects (and deer!).

It turns out that climate change has both positive and negative consequences for insects. Warmer temperatures mean longer breeding seasons for many insects, but droughts and increasing forest fires mean loss of habitat, and heat waves can kill off insects that are sensitive to higher temperatures.

Finally, invasive species have also contributed to the decline of insects. This includes other invasive insects (such as European hornets that kill honeybees) or invasive species such as exotic fish (like goldfish) which if released into the wild will eat native insects and disrupt the balance of a local ecosystem.

The best things we can do to slow and hopefully reverse the decline of our insects include using better alternatives to pesticides and educating the public on why they are critical to sustainable life on Earth (and not just pesky pests). We can also help by incorporating more bug-friendly touches to our human-made environments: grass strips, hedges, microhabitats like roof gardens or these tiny forests that support diverse life on an extremely small footprint.

At your house, how might you support insect growth? After all, those beautiful flowers in your yard wouldn’t bloom without the help of our pollinators!

I'm not sure how much of a decline there has been in New Zealand. Certainly, some of our native insects are endangered by introduced mammals like rats, mice and hedgehogs. (Non-native) honeybees have also declined due to the varroa mite. Mosquitoes, on the other hand, seem to be doing well.

Living in rural NE Georgia, Ive noticed the lack of bug smears on the windshield for several years now.

What’s even more disturbing to me is the the almost complete disappearance of frogs and toads on the roads. Ten years ago when a typical late afternoon summer rain shower wet the roads one needed to drive very carefully to avoid squashing the hundreds of frogs on the pavement.