What is the rarest color in nature?

And why aren’t there any green seashells?

This mountain girl is not much of a beach person, but I do love going in the off season to the Florida panhandle, otherwise known as The Forgotten Coast – where the only grocery stores are Piggly Wiggly and the nightlife consists of spotting nesting sea turtles. Andrew and I recently made the journey to Florida to eat seafood and walk the beach just long enough to earn our next seafood meal.

The area near Apalachicola is made up of acres and acres of wildlife management areas and protected shorelines. This is where the Apalachicola River, formed by the combination of Chattahoochee River and the Flint River, empties into the sea and feeds the famous oysters of Apalachicola Bay. This area is rich with wildlife: bald eagles, herons, pelicans, dolphins, starfish, and, of course, millions of seashells.

It was while wandering the beaches, perusing the shells beside the rhythmic sea, that I began to wonder about color. It seemed that, while the shells were gorgeous, they tended to come in colors on the “hot” side of the spectrum: red, orange, yellow, and a sort of beige. I found some grays and even a few purplish specimens, but I couldn’t find anything green. I’d intended to make a “rainbow” assortment, but was missing the cooler end of the rainbow. Do green seashells even exist?

That, in turn, made me wonder…

What is the rarest color in nature?

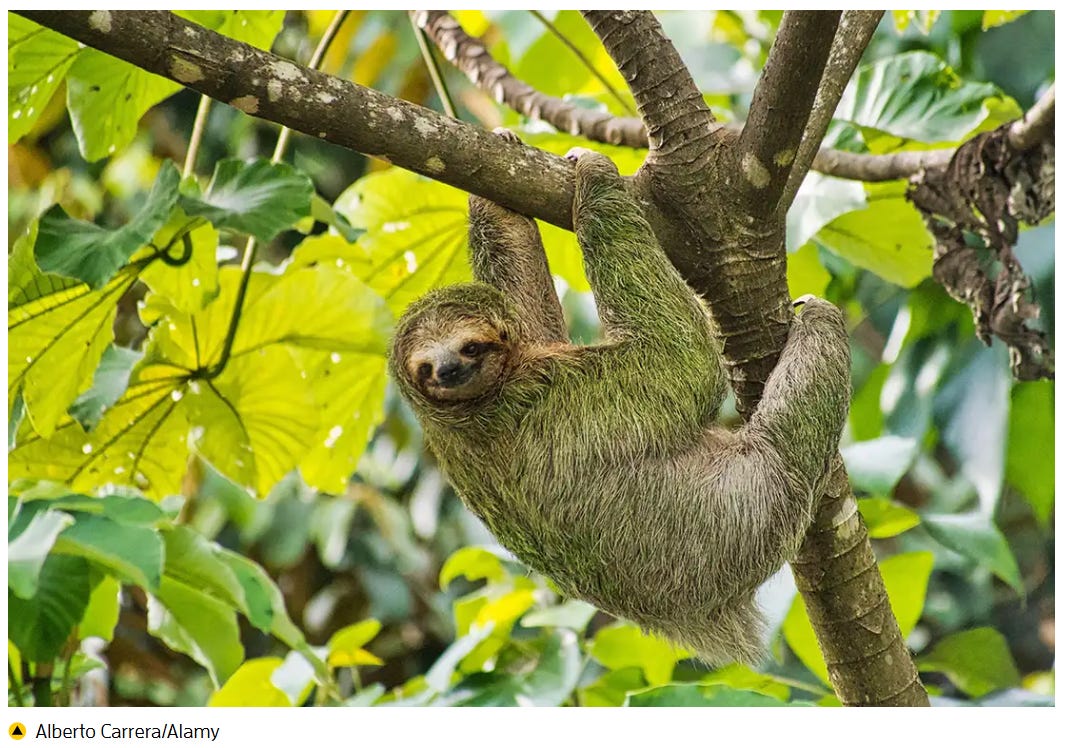

Green is NOT the rarest color – that’s obvious because chlorophyll provides such pervasive color saturation in leaves around the planet. However, I did discover that no mammals appear green because they (we) lack the ability to produce green pigment. Snakes, birds, and even fish can, but not us mammals. Sometimes sloths appear green, but that’s due to algae growing in their fur.

The color that is the rarest in nature is BLUE.

Wait – we’ve all seen blue flowers, blue birds, blue butterflies – I even included a picture of a blue tarantula in a previous newsletter.

Blue doesn’t seem that hard to spot in nature, right?

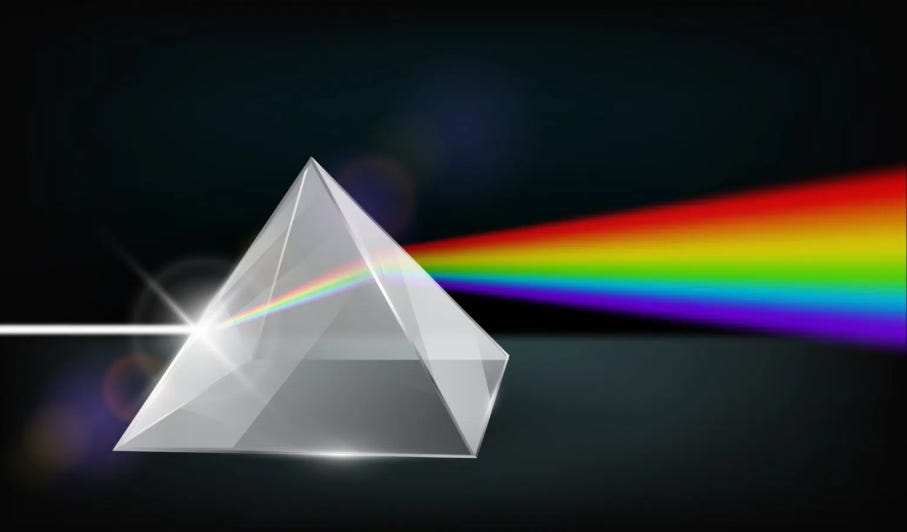

Actually, the pigment blue is very rare in nature. Let’s take a blue jay as an example. The feathers of a jay aren’t blue due to a blue pigment the bird produces. Rather, it’s blue because of structural color, meaning their feathers are covered in microscopic beads that scatter blue light to give the illusion of blue-ness.

The same is true of blue butterflies, such as the Blue Morpho, which has ridges on its tiny feathery scales that reflect blue wavelengths of light.

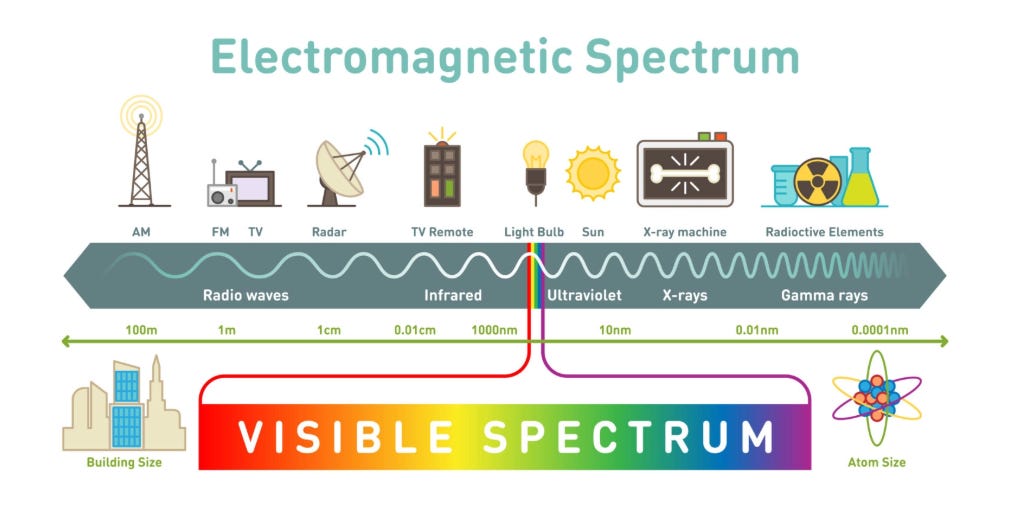

Basically, light comes in a full spectrum of colors, most of which is invisible to human eyes:

Colors on the red/warmer end have a lower, more laid-back frequency while colors on the blue/violet end have a higher frequency. Most blues we see in nature are actually a trick of the eye due to structural color – the object is shaped in such a way as to bend the light and scatter the light into blue wavelengths.

The blue eyes I wrote about a few weeks ago? Not really blue. Blue eyes don’t actually have blue pigment – it’s, again, a trick of the light, a scattering of the wavelengths of light that make the eye appear blue, whether it’s a person, a Siberian Husky, or a horse.

The sky looks blue for the same reason – light from the sun bounces off of molecules in the air and high-frequency blue light scatters the most. Actually, the color violet has an even higher frequency than blue, and if our eyes could process it, the sky would appear to be violet.

However, plants with blue flowers aren’t using structural trickery to get their blue hue – and yet they still don’t produce blue pigment. Most plants are actually a reddish color due to red pigments called anthocyanins. Of course, chlorophyll covers up those reds in the stems and leaves for most of the year. But for the very few that produce blue flowers (less than 1 in 10!), the plant alters the anthocyanins to create a blue hue. “They do this through a variety of modifications involving pH shifts and mixing of pigments, molecules and ions,” says David Lee, author of “Nature’s Palette: The Science of Plant Color“.

It’s just too complicated, molecularly, for organisms to create the structures needed to produce actual blue pigment. Evolutionarily, it’s easier to tweak other pigments or trick the eye with structural color.

One of the few organisms to actually create blue pigment is the obrina olivewing butterfly, which has small blue bands on its wings. I can’t find any information on why this particular insect creates blue the old-fashioned way, so if any of you have any insight, I’d love to hear about it.

As for the green seashells I was missing on my trip to Apalachicola, my research revealed that there are green seashells, though they are harder to find. Green turbo shells are a beautiful green color, as are green limpets, but neither are common on the panhandle of Florida. Green seashells, it turns out, are green due to pigment – no trickery or sleight of hand involved!

Across the world, blue is the favorite color of most humans – a poll found that a majority of people in every country prefer blue. Perhaps, on some level, we realize and value its rarity. Regardless, much of the blue we see is not really there at all, and is simply a trick of the light.

George Carlin used to joke that there was no blue food. Even blueberries, he said, were purple.

Chartreuse