Last week’s walk with the hiking club was an exercise in self-control (along with the usual forms of exercise). We headed to Springer Mountain, the renowned southern terminus of the Appalachian Trail. Although I grew up along the AT in North Carolina and have day-hiked many sections of it, I’ve never been to the famed beginning of the trail.

It was a magnificent day, bluebird sky, temps in the 60s to 70s F and a forest that was green, green, green with new growth and flowers. We started on the Benton MacKaye Trail (BMT), named for the founder of the AT, and headed two miles up to the summit before wandering another four miles along both the AT and the BMT on our way back to the cars.

But only half a mile in or so, we started noticing tons of spider webs crisscrossing the path. I was in front, spending lots of time wiping the webs off my face and arms, until I began to notice inchworms dangling from the trees and realized – these weren’t spider webs. Before long, the caterpillars were everywhere, sometimes three or four suspended near each other.

I grabbed a stick to clear the path in front of us, devising a circular, figure-eight motion that swept up as many creatures as possible. It seemed I was missing a good many, however, because I could feel them landing on the back of my neck and arms. Everyone ended up stopping about every quarter mile to pick creeping caterpillars from each other’s backs and hair like a group of gorillas grooming each other.

That’s when we could hear the rain. What sounded like the gentle whispery beginning of a spring shower was actually millions of caterpillars pooping on our heads.

The folks who wore hats were pretty smug about it.

Despite all this, it was too pretty a day to get upset so we all just kept picking off caterpillars and trying not to think about what was crawling in our hair.

What was fascinating about these caterpillars is just how widespread they were – we encountered them for about three full miles, probably hundreds of acres of forest were affected. So much of the tree canopy had been consumed that some trees appeared to have no leaves at all, while others had just slivers of greenery left.

The thin upper canopy meant the forest floor was receiving a huge amount of sunlight it normally wouldn’t have. The ferns were loving it, but there was also a lot more grass growing along the trail than I’d seen in other places. Interestingly, the edge of the caterpillar’s domain was very abrupt – suddenly we were in shaded forest, surrounded by healthy leaves, and I was able to gratefully drop my caterpillar-catching stick.

What were these caterpillars? What would they turn into, and would that creature be just as destructive to the forest? Could these trees survive, or would this infestation kill them? Do they come back year after year in the same area? Do they have a predator? There were a lot of questions to answer…

Why is it raining…caterpillar poop?

The freefalling poop has a scientific name (of course it does): frass. The term applies to the excreta of insects and chances are, if you’ve been hiking in the woods you’ve ended up with it in your hair. Caterpillars, beetles, and other insects – when they gotta go, they gotta go, and that means frass that falls to the forest floor and fertilizes the plants below. Of course, someone’s always got to be different, so there’s also the thistle tortoise beetle larva that collects its frass and carries it on its back to discourage predators:

Trying to figure out what type of caterpillar was ravaging the forest on Springer Mountain was harder than I thought it would be. One hiker with our group thought they were Gypsy Moths; however, those caterpillars are the fuzzy, stinging kind and fortunately have not been regularly seen in Georgia yet.

Another member of the hiking group, who wasn’t able to attend but saw the pictures, felt like they were the larva of Contracted Datana Moths. However, those caterpillars have bristles down their sides and don’t appear until August and September.

Instead, I’m pretty sure what we saw were Spring Cankerworms. They are loopers, another term for inchworms, and “have three pairs of hardened, thoracic legs on the thorax and two pairs of soft, fleshy prolegs on the abdomen, with a gap in between that causes them to use an ‘inching’ movement to crawl along surfaces (source).” Both their description and their inchworm action match what we experienced.

The adult moths emerged from cocoons a couple months ago, in late winter. Interestingly, the females don’t have wings:

They quickly mate, then the females crawl up trees to lay their eggs. When they hatch, tiny caterpillars are everywhere, as evidenced by the shothole effect we saw on the leaves. As they get bigger, they eat the entire leaf except for the midrib and larger veins. Check out this short, highspeed video of Contracted Datana caterpillars ravaging a set of leaves (click the photo):

After about 6 weeks, the caterpillars have eaten their fill and are ready to descend to the forest floor on tiny threads to make their cocoon – that’s the stage where we encountered hundreds of them in on our hike. They had full bellies and were ready for a nap until the end of next winter.

What about the trees? Can they recover? For otherwise healthy trees, a single season of defoliation won’t hurt the tree since it can leaf out again in a few weeks (as I explored in this story about early frosts), but if the tree is already weak from drought or other infestations then losing that much greenery can be deadly.

Gypsy Moths, which have been renamed Spongy Moths so as not to be disparaging to actual gypsies, can be very damaging to forests. During the 100-year period between 1920 and 2020, Spongy Moths defoliated more than 95 million acres of trees. That, in combination with the fact they sting and can cause allergic reactions, is enough of a reason in my book to change their name. The Gypsy people have enough to deal with.

Treatment for Spongy Moths includes spraying a naturally occurring soil bacterium from the air, a solution that doesn’t affect other species.

On the other hand, cankerworms, whether they’re the Spring or Fall variety, have enough natural predators that they usually don’t wreak havoc like the Spongy Moths. Their predators include parasitic wasps, other insects, birds, and mice. Late frosts can also kill them off.

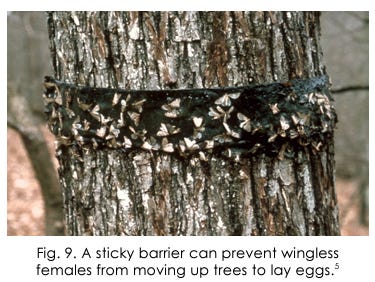

One simple treatment if you know you’ve got them in your area: in late winter, wrap tree trunks with cotton batting, filling cracks in the bark females could crawl under. Then cover the batting with plastic wrap and layer on top a sticky goo such as Tanglefoot. This prevents the females looking to lay their eggs from making it very far up the tree.

I’d be interested to hike Springer Mountain again in a few weeks to see if the trees have been able to recover. By then, the caterpillars should be mostly gone, underground and getting a long summer/winter’s nap.

I actually have one other memory of raining caterpillar poop and it involved an outdoor picnic where it took us an embarrassingly long time to figure out the potato salad really didn’t have THAT much pepper in it. So, I can go ahead and pretty confidently say the poop isn’t poisonous…

Weird Nature:

The Thistle Tortoise Beetle’s much more glamorous cousin:

Heather you consistently make my day

Heather, this has to be the most entertaining as well as informative Substacks I've read in the last couple of weeks. Restacking