How do live oaks survive a hurricane?

I’m fascinated by trees. They are woody plants, made of similar stuff as a forsythia bush or poke weed plant, and yet they tower over me, making me feel like an ant wandering between blades of grass. They are enormous, stretching 40, 60, 80 feet in the air like solid cliffs and yet they bend with the wind. While on a recent trip to Florida I was reminded of the poetry of live oak trees in particular. Along with being the state tree of Georgia, mature live oaks just exude stately wisdom with their limbs stretching in all directions, some reaching for the sky, others curving back down and even touching the ground. Their gnarled trunks form footholds that beg a child to climb into their low hanging branches. I always imagine Shel Silverstein’s Giving Tree to have been a live oak, perfect for climbing and swinging and sitting in the shade.

With their branches being so heavy and often stretching in such odd contortions, it occurred to me to wonder:

How do live oaks survive a hurricane?

It seems like the strong winds of a hurricane would strain the twisted branches to their breaking point. They’re so enormous, surely they catch a lot of wind load and would topple over in a storm, right?

Well, it turns out that live oaks are actually designed to survive the stresses of hurricanes. Out of approximately 700 live oaks in New Orleans, only four were killed by Hurricane Katrina. They may lose some branches, leaves, and large clumps of Spanish Moss, but the trees themselves are built to survive. There are several reasons for this…

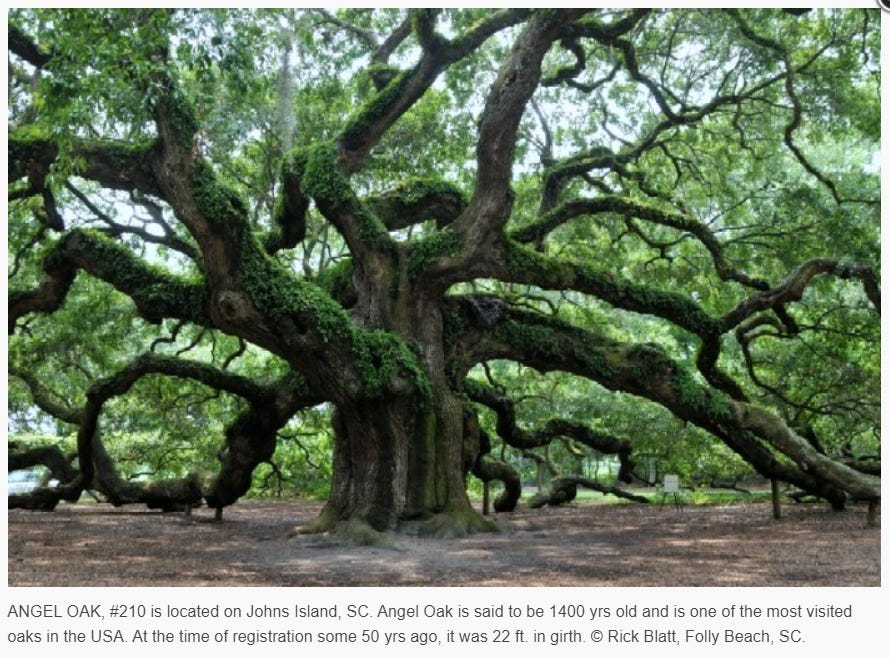

One reason is that the wood of their trunk and branches are spiraled, so they flex in the wind. You can see the twisting of the trunk and branches in this gigantic example:

When strong winds blow, the twisted wood allows the tree to flex and bend rather than crack.

Another reason live oaks are great in hurricanes has to do with their shape. Live oaks are considered to be a medium height tree that are normally around 40-65 feet high. They have a low center of gravity, with main trunks that are 4-6 feet in diameter. Because their crowns spread so far out, the spread of their branches is oftentimes a greater distance than their height. This short and fat profile means that during storms they may lose branches and leaves but often survive hurricane force winds.

Compare the live oak on the left below with the red oak on the right. It begins to make sense how the gnarled live oak, spread out and squatting on the forest floor, could avoid toppling over in hurricane force winds, whereas the red oak, being top heavy and extremely tall, will likely catch a great deal of wind and split or fall over.

Another advantage of live oaks is that the main branches spread out from the base without a main axis, creating a large crown or canopy. You can see this in the photo above – at about 15-20 feet, all the branches go outward, whereas the red oak (and most trees, it seems) stretch upwards with a main trunk that reaches high into the sky, like a sail in the wind.

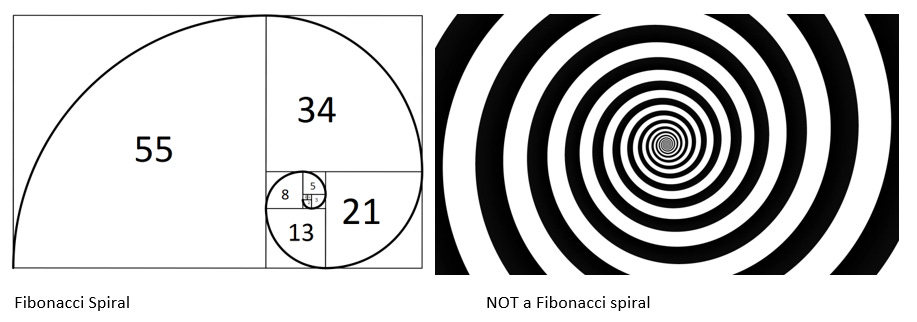

Finally, one of the more fascinating survival skills I discovered about the live oak has to do with the spiraling of its leaves on the branches and something called the Fibonacci sequence. If you’d like an excellent, somewhat longer explanation of how the Fibonacci sequence works, check out this video. But an extremely simplified version is that someone named Fibonacci discovered a simple pattern of numbers: start with 0+1=1 Now add the answer to the previous number in the problem (1+1=2) and repeat:

0+1=1

1+1=2

1+2=3

2+3=5

3+5=8

5+8=13 and so on

This number sequence explains a growing spiral that shows up in nature over and over again.

The Fibonacci spiral appears in seashells, how seeds are arranged on a pinecone, and even the curvature of hurricanes. In live oaks, the spiral shows up in how the leaves curl around each stem:

This spiral pattern not only maximizes photosynthesis, as this amazing 7th grader discovered, but it also allows the wind to pass through the leaves more easily and not catch a large wind load. Compare that to a hemlock branch that doesn’t spiral and would act more like a sail to catch the wind:

All of these characteristics put together helps explain why we still have live oaks that are several hundred to more than 1,000 years old along the coastlines of the Southern U.S. The Live Oak Society celebrates these ancient trees by cataloguing and mapping the largest specimens. Any oak that has a circumference larger than eight feet is allowed to join. The president of the society is the largest living live oak, currently the Seven Sisters Oak in Louisiana, with a girth of 38 feet. Members of the board are other oaks that are the runners-up in size. Only one human – the chairperson – is allowed in the society, presumably so she can keep the website going with her handy opposable thumbs.

So, I’ve learned that live oaks are not only poetic and immense, but also very cleverly evolved to adapt to the harsh weather they sometimes find themselves in. And thank goodness, because now we can climb oaks that have been here since Hernando de Soto landed in Florida in the 1500s. If these trees could talk, what would they tell us they’ve seen?

If you liked this post, please share it with others!

Detritus

Think Like a Tree - a cool video illustrating how live oaks survive storms

More about Southern live oaks

Cool examples of the Fibonacci sequence in nature

The Fibonacci sequence in nature - a mathematical website with lots of theory

The Live Oak Society - scroll to the bottom to see photos and read about these record setters

What are your thoughts? Do you love live oaks or other trees? I’d love to know what you think!