How do large holes form in river rocks?

...and some thoughts about lightning

Welcome to Natural Wonders, where I hope to pique your interest each week by sharing some fascinating questions and answers about natural phenomena. If you’re new here or if someone forwarded you this email, you can subscribe below.

Check out past posts by going here and see who I am and what Natural Wonders is about here.

A few weeks ago, I went on a hike with my local club along the banks of the Chattooga River. The river is most famous as the filming location of Deliverance, a movie which I have purposely never seen because I don’t want to ruin my view of the river. It is designated as a Wild and Scenic River and it is truly a remote and beautiful place.

I took the picture above while looking down on Raven’s Chute rapid on section IV of the river. It was a beautiful view, but the other hikers and I were confused by the dark circle to the left of the rapid (or river-right as paddlers would say). We couldn’t tell if it was an object on the rocks or a hole.

When we hiked closer to the falls, we saw that it was a fairly large hole in the rock:

My dad had been a raft guide on the Chattooga for many years, and when I asked him about the hole he laughed and said, “Ah, yes! That’s the pothole at Ravens – it actually bores all the way through the rock and connects to the river underwater on river-right. Sometimes, when the water’s a little higher and just skimming over the top of the pothole, raft guides would jump out of their raft and dive into the hole, making the folks in their raft think they’d drowned until they popped back up downstream. Fun times!”

Fun times indeed… It turns out raft trips oftentimes stop at Raven’s Chute and let guests who are feeling brave swim through the pothole into the river below. You can see that here as a paddler wearing a GoPro gets flushed through:

It’s a fun/scary experience, I’m sure, but it also made me wonder about this hole in the first place – how did it get there? Why is it the only one? How come it’s so wide and deep? It led me to my next Natural Wonder:

Where do holes in river rocks come from?

These circular depressions and holes in rocks are called potholes. They can form in very turbulent streams, but you can also find them in ocean bedrock and underneath glaciers. The holes are formed when water consistently swirls in a circular current of water over a large section of rock. The swirling water carries with it rocks, sand and small pebbles. Over time, these wear away at the rock:

Just like everything I research for this newsletter, as soon as I started learning about potholes I began to see examples of them everywhere. Here is a small one I found with pebbles in the bottom:

And nearby I found evidence of a tiny pothole beginning to form:

I found these on Moccasin Creek, which is a turbulent, fast-flowing creek in North Georgia. Who knows how many more potholes might have been forming underwater, invisible to me?

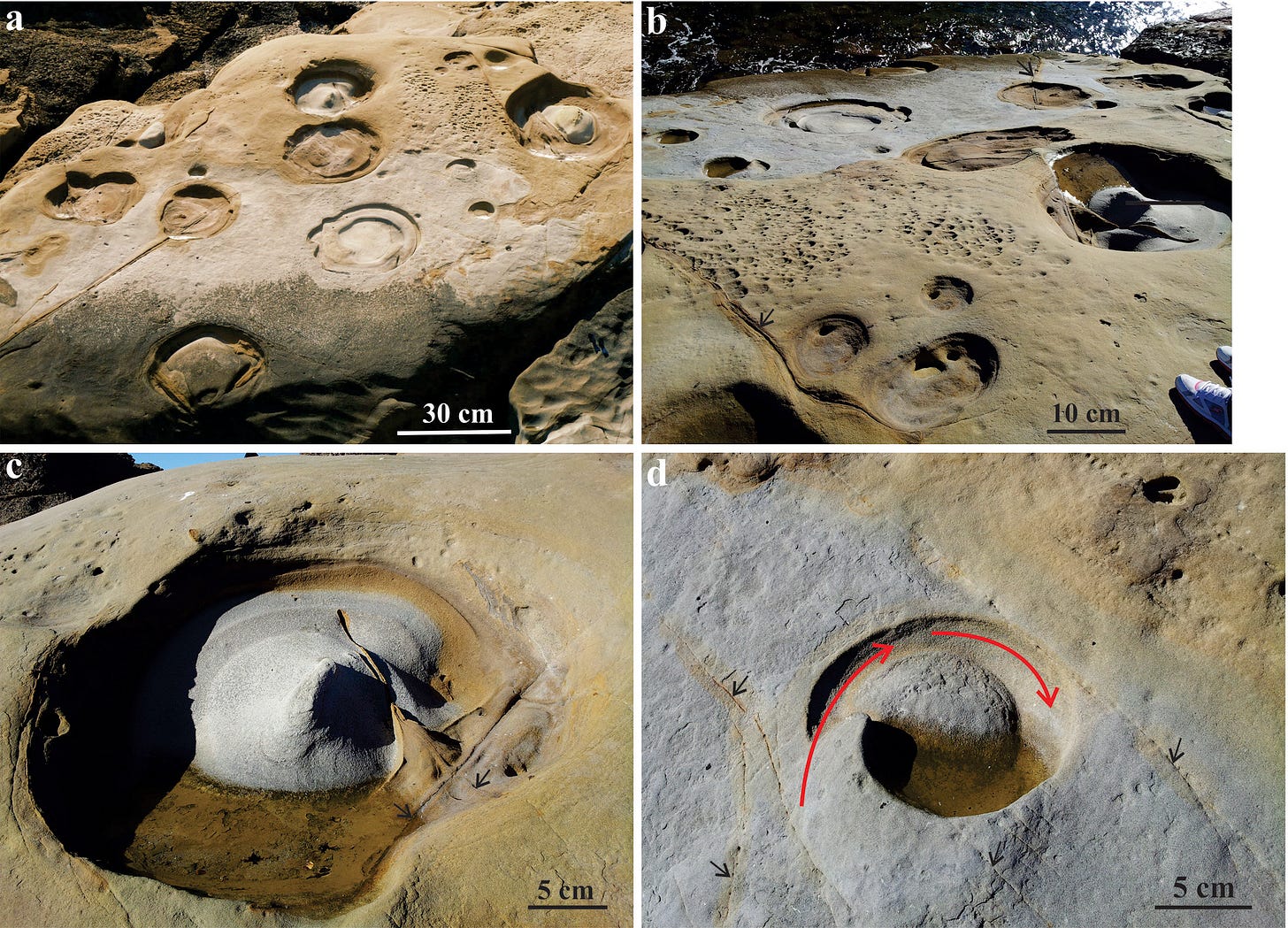

It turns out with potholes that form in streams, the depth increases faster than the diameter of potholes because the size of the grinding stone is generally large and wears away the bottom faster than the sides. However, with potholes in oceans, the reverse is true – potholes are shallow, but wider:

As you can see in the photos, marine potholes oftentimes leave a hump of rock (or “central island”) in the middle of the pothole. These potholes tend to be wider than they are deep because the ocean generally isn’t as strong as a stream – any heavy rocks remain in the bottom, protecting the base from erosion, while smaller sand and pebbles swirl around the edges and wear it down with the flow of the tide.

Sometimes, smaller potholes combine to form larger potholes. This is what has happened with multiple potholes in the famous Antelope Canyon to produce these poetic curves:

All of this investigation into circular holes in stone made me think of another related question I had:

Are the round depressions in large rock outcroppings caused by lightning strikes?

When I’ve hiked on high peaks with large areas of exposed rock, I’ve been told that the round divots in the rock face were the result of lightning:

This, it turns out, is a myth. The small indentions are called weathering pits and they’re created when water collects in a small area and combines with acids from neighboring plants to wear away at the rock. Pools that hold water for several weeks or more are called “vernal pools.” They can even contain tiny, translucent shrimp whose eggs somehow survive the dry season and hatch when the pits fill with rainwater.

When lightning strikes rock outcroppings, what actually happens is an extremely hot mini-explosion that can melt the rock’s surface and create a bluish-black glaze. The rock is heated to over 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit, twice as hot as lava, and produces fulgarite under or on the surface. Fulgarite is melted rock that oftentimes looks glassy and black, like this example from Mount Thielsen, the “lightning rod of the Cascades” in Oregon:

It looks nothing like the beautiful “lightning glass” from the movie Sweet Home Alabama, which was actually created for the movie set by glass blowers.

Now that I think about it, this makes sense – lightning striking a rock would naturally spread outward along the rock face and not just create a circular depression in the rock like I’d always believed.

So, along with adding inosculation and marcescence to my vocabulary, I can now confidently use the word fulgarite in a sentence and “pothole” to mean something other than a car-eating crater in the street.

Have you seen potholes or lightning strikes before? I’d love to know where you found them and what they looked like.

Nature Break: Take a walk alongside a young, tumultuous creek or small river and look for potholes. It must be a rapidly-moving river — old, slow-moving rivers don’t have the power to create these holes. Can you find them in various stages of formation?