How do animals survive when it’s this freakin’ cold?

(and will the polar vortex kill off our invasive spiders?)

Merry Christmas, Happy Hanukkah, Joyous Kwanzaa, Wonderful New Year and all the holidays to each and every one of you! I was going to write about trees and oxygen again, a continuation of last week, but then the North Pole winds came to visit so I put that issue on ice (so to speak)…

If you live in North America, you are probably aware that much of the U.S. and parts of Mexico have been visited by a warp in the jet stream that brought frigid arctic temperatures to places that are not at all prepared for it:

Arctic blasts like this are becoming more common as climate change destabilizes the jet stream. Here in Georgia, our average low winter temperature is usually in the mid-30s (2° Celsius), but for three days this past week we never rose above freezing at all. Actual temperature dipped into the single digits, with windchills well below zero.

We southerners are not used to this. Most folks around here don’t go through the yearly ritual of putting away the previous season’s clothes – I’ve had students wear shorts to school in January when they clearly should have had more supervision with clothing choices.

During this latest, record-breaking cold snap, I had the luxury of spending most of it inside – when I did venture out, the icy wind numbed my cheeks in less than five minutes. Opening my mouth made my teeth hurt. Any crack in my clothing – I need taller socks – was instantly ferreted out by the maniacal wind. I took pictures of ice forming in our creek but could only stand to be outside for about 15 minutes.

It made me wonder – how are our southern animals withstanding the cold? Can the deer, who generally just bed down under trees, maintain normal body heat for three frigid days? The ground is frozen solid, so how will the moles, frogs, and even rabbits survive? Birds don’t even have fur, so will they make it? Will we have a large die-off of wild animals because they aren’t prepared for this arctic blast?

How do animals survive when it’s this freakin’ cold?

I decided to begin by digging in to how animals from the polar regions withstand the cold. Animals in the north and south poles of our planet (and those regions nearby) have several choices when it comes to bitter cold: migrate away to an area closer to the planet’s midsection, hibernate during the coldest season, or adapt in some way to be able to stay awake, hunt, and thrive.

Migration

Many birds famously migrate to warmer climates, but the reason why might surprise you. They don’t leave because the temperature’s too cold – they move because their sources of food generally disappear with the coming winter. Birds that eat berries, nuts, and insects head toward the equator so they won’t starve. Otherwise, their bodies are fairly well adapted to handle the cold – even their featherless legs. For instance, gulls and other arctic birds are able to keep their feet warm, even while standing on frozen ice, because they have a concurrent heat exchange system in their legs. The arteries carrying fresh blood to their extremities run very close to the veins carrying cooler blood back to their hearts, and this nearness rewarms the blood in their skinny, exposed legs.

So, even the birds that flew down here to the south to escape Canadian winters – like Canada Geese – are equipped to handle the cold. Their winter food source is still here and, fortunately, not covered in snow.

Hibernation

Most polar animals are endothermic, meaning they’re warm-blooded, producing their own internal heat. Ectothermic animals, such as reptiles and amphibians, rely on the warmth of the ambient air and sunlight to warm their blood, and are therefore nonexistent in the polar regions.

Outside of the poles, salamanders, lizards, and turtles have adapted by entering a state of torpor when cold weather strikes. For alligators, this hibernation is called “brumation” and it’s wild to see – the gators slow down their metabolism and suspend themselves vertically with their snouts just out of the water so they can breathe:

Other ectothermic animals have adapted to be able to survive the actual freezing of their own tissues during frigid spells. For instance, Wood frogs live as far north as northern Alaska and as far south as Alabama. They are distinctive in cold weather because rather than entering a state of torpor like most reptiles and amphibians, they take it one step farther -- their hearts stop, their breathing ceases, and they flood their cells with antifreeze while allowing the space between those cells to actually freeze into ice.

While many frogs and toads have this adaptation and up to 70% of the liquid inside can freeze without harming them, the animal could die if it freezes completely or if the temperature drops too quickly, when it is not prepared. In this latest polar blast, some areas had extremely rapid temperature drops – up to 47 degree drop in two hours in Denver, Colorado, for example. This may have been deadly for animals that attempt to survive by producing cryoprotectants in their tissues.

Adaptation

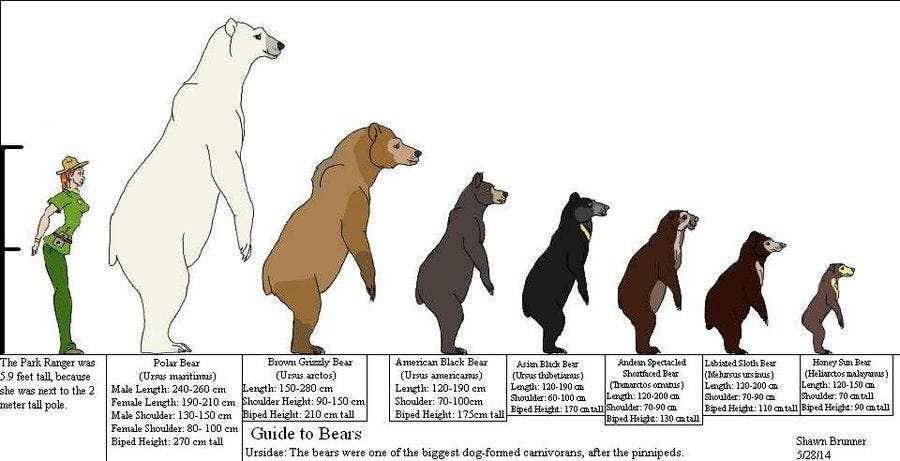

How do warm-blooded animals endure in extreme cold? First, it pays to be large. A law of nature states that the further north you go (or south, from New Zealand!) the larger the animal. They have proportionally less surface area as compared to their body mass, making it easier for the animal to heat itself. For instance, here in the continental U.S. members of the deer family (cervids) are generally small and dainty – whitetail deer with their long, thin legs, or even the tiny key deer of the Florida Keys that max out at around 65 pounds. The farther north you go, the bigger the cervids – elk, moose, and caribou have large bodies and thus better ability to heat themselves. It’s the same with bears:

Secondly, warm-blooded animals need insulation in the form of fat (like the Alaskan bears competing in Fat Bear Week) or feathers and fur. Whitetail deer’s ability to survive the coldest months usually comes down to how much fat they were able to layer on during the fall and early winter, when acorns and other food was plentiful. In the deepest winter months, not much is available except for stems, buds, and bark, which don’t provide good nutrients but do at least generate internal heat as their bodies work to digest them (I’ve written before that deer’s winter eating habits may be why beech trees keep their leaves all winter).

The deer and other warm-blooded creatures experiencing this week’s arctic blast are likely fine as long as they fattened up a couple months ago and aren’t weakened by disease or injury. It might be a different story, though, if polar winds arrive in February after many non-hibernating animals’ fat stores are depleted.

What about invasive species?

It’s no secret that I’m not a fan of our invasive Joro spiders. They originated in Southeast Asia and have thrived in our humid, warm climate in Georgia. Could this multi-day polar blast of below-zero weather kill all the Joros?

In the past, unusually cold weather has killed 95% of stinkbug populations in some areas. In 2010, an arctic blast dropped as far south as the Everglades where invasive Burmese pythons have decimated the local population of raccoons, opossums, and rabbits. Lovers of local wildlife were hopeful the cold would take out most of the pythons, and it did – there were a lot of dead snakes in those swamps. But some survived, and those that survived carried genes that allowed them to tolerate the cold. Those survivors reproduced and guess what? We now have a new generation of snakes that are genetically tolerant of colder weather.

A polar vortex in 2019 killed off many invasive insects like the emerald ash borer and the hemlock wooly adelgid (which can’t withstand temperatures below -4F), possibly up to 80% of their populations. But 80% means there is still 20% left to breed.

With our Joros, unless every single one is killed – an unlikely scenario – the species will recover and likely even “build back better” by adapting itself to the colder temperatures, thus making themselves more likely to survive future cold snaps.

Will Georgians still be dealing with enormous webs and hand-sized spiders in the future? I’ll let you know next summer…

Detritus:

The polar areas of our planet are so cold for so long that nature has imposed a size limit of 13mm (about half an inch) on cold-blooded animals that live there. Anything larger and the animal wouldn’t be able to warm itself enough before the temperatures dropped again. The 13mm flightless midge is Antarctica’s largest and only insect and spends about 9 months of the year frozen solid.

I’ve written before about wooly worm caterpillars that live for 14 years, freezing each winter and thawing out each spring, before living as a moth for a mere 24 hours.

Ptarmigans are a type of grouse that don’t migrate from the cold northern climes but instead molt each year into pure white feathers to blend into the snow. They eat dry leaves and buds and, since there’s no liquid water to be found, they eat snow for its moisture content. Each fall their feet grow tiny projections called pectinations that act like snowshoes in the ice.

Weird Nature:

If you liked this issue, please click the “like” button below - it makes me happy and also raises the profile of this newsletter!

I was recently doing lots of pondering about wildlife survival here in Wisconsin when the temp was minus 15 F but with windchill minus 37 F

Excellent article- Beech trees add so much to an otherwise barren winter forest scape. We have only a few in our woods and would like to encourage more. Did not know they spread by their roots. I’ve read that there were extensive forests of them before deforestation occurred.