Welcome to Natural Wonders! More than a month ago I was all set to write this issue about sensitive briar when I got interrupted by an enslaving horde of ants and became sidetracked into writing about insects and spiders for quite a few issues. If you’re a new subscriber and would like to check those out, click here.

During college I had a campus job at the onsite preschool, and I loved to listen to the children’s filter-less comments as they tried to make sense of the world around them. One windy day we had to come in early from the playground because of the danger of falling limbs. A little boy, upset at having playtime interrupted, angrily told me that “if the trees would stop moving around so much, we could keep playing!” He thought the wind was caused by the trees thrashing their limbs and moving the air around the playground.

That would be an interesting world to live in… Imagine if the trees that surround us could move at will, waving their long limbs as they towered 60 feet overhead. I think of the violent movements I’ve observed some trees make during a storm – if trees were able to move like that of their own free will, it would be more than a little terrifying, I think.

The fact that trees can’t move by themselves is one of the main characteristics that separates them from animals. Trees, and most plants for that matter, are stuck wherever their original seed landed, and they survive (or not) based on how well they make do with their immediate resources. They can’t move a bit closer to the creek when they’re thirsty or dodge another tree when it falls in a storm. Plants simply can’t move on their own – it’s what makes them plants, right?

Except that some of them can.

I can’t remember who first showed me sensitive briar as a child, but I’ve always thought it’s a fascinating plant. Even now I can spend a good deal of time squatting next to a plant, stroking the leaves to watch them close. Plants simply aren’t supposed to be able to move like that!

Why, of all the plants, is this one able to move? Are there others that can? Venus Flytraps are one example – what other plants can move? How do they do it? (They don’t have muscles) And what’s the purpose behind this movement?

How (and why?) are some plants able to move on their own?

Sensitive briars are a type of Mimosa (oddly, Mimosa trees, though related to sensitive briars, are not a true Mimosa). They live all over the southeastern United States in wild, sunlit areas.

Why do they move when touched? I can understand why a Venus Flytrap moves – it’s capturing its next meal. But sensitive briar is expending a lot of energy to close its leaves – and by closing them, it prevents photosynthesis from occurring until it opens back up. It’s essentially starving itself for a short while!

Scientists think the movement is a protective mechanism against predators – when a deer or other hungry animal tries to munch on the leaves, they close in on themselves, exposing the thorny briars underneath. Those briars point backwards on the stem, meaning they’re extremely painful if an animal tries to strip the leaves off.

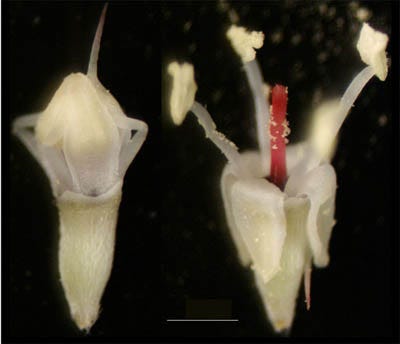

This ability for a plant to move its leaves when touched is called thigmonasty. When a sensitive briar is even lightly touched, the plant releases an electrical impulse down the stem of the plant. Each set of opposing leaflets is connected to the stem with a tiny hinge called a pulvinus; as the impulse passes each hinge, the cells on the underside deflate and send water to the upper cells causing the leaflet to become limp and fold up. A cool video illustrates the process here.

As if the fact that it can move isn’t enough, scientists have shown that sensitive briars can learn, as well. When they repeatedly caused a plant to close its leaflets by dripping water droplets on the stem, the plant became habituated to the water and no longer closed up. However, it still responded quickly when touched by a human, showing it had learned to distinguish between a repetitive stimulus that wasn’t dangerous and one that potentially was.

What other plants can move?

Another plant that is able to move when touched is Jewelweed, which I grew up calling by its common name Touch-Me-Not. The seedpods of Jewelweed are spring-loaded – all it takes is a tiny squeeze for the internal seeds to go flying:

The purpose here is pretty obvious – the plant wants to disperse its seeds as far as possible, so it has developed the ability to grow tension-filled pods that are extremely sensitive to the touch. Another possible purpose could be to prevent birds from eating the seeds – this birdwatcher noticed Grosbeaks popping the seedpods while being able to eat very few as they flew in all directions.

Some plants have developed slingshots for catapulting pollen into the air. The dogwood bunchberry randomly lets loose a puff of pollen for the wind to disperse. The release is too quick for the eye to see – it takes less than half a millisecond to explode.

Amazingly, that’s not the fastest moving plant, however. White Mulberry Trees sling pollen from their flowers at 380 mph, about half the speed of sound. It takes an extremely high-speed camera to capture their movement, which is thought to be at the outer limits of what plants are capable of.

Of course, Venus Flytraps move quickly too – they take only 100 milliseconds to “eat” an insect that has the misfortune of tiptoeing across its leaves. Each leaf has hair-like triggers arranged around its outer edge. If an insect touches a hair, the plant prepares to close, but waits until another hair is touched, just to make sure it doesn’t waste energy unnecessarily.

But the strangest one of all has to be the telegraph plant, also known as the dancing plant. It lives in southeast Asia, and moves its leaves all on its own without having been touched. This video was recorded in real time (not sped-up):

Most plants can move their leaves (think about sunflowers that slowly tilt to face the sun as it treks across the sky), but they usually do it so slowly our simple human eyes don’t notice. Why does the telegraph plant move so quickly? There are a couple of theories: the smaller leaves might be sampling the sunlight so the bigger leaves can slowly move to optimize their best angles. Another theory is that the movement deters predators or mimics butterfly movement to keep butterflies from laying their eggs on them (and then eating their leaves when they hatch).

If plants can move, and learn, and even dance, then perhaps we’re closer to living in the world of that opening preschooler than we think. If plants respond to touch, does that mean they’re sentient beings? Some scientists have argued that trees can feel pain. Do trees and plants have brains that are just shaped or organized differently than ours? Would that change how you feel about trees, if we discovered they do?

Nature Break: Lay down on your lawn or in the forest and look up at the trees on a breezy day. Watch the small movements as the branches wave back and forth, the leaves twisting on their stems. Now imagine the tree is able to control that movement. How would you feel?

Weird Nature:

Detritus:

Plants in Motion is an older site from a professor at Indiana University that has videos of lots of different plants that move – many more than I covered here.

Bladderworts are another plant that moves: they set a trap where an insect is sucked into a bladder filled with sap that slowly digests it.

Telegraph plants (AKA “dancing plant”) get their name because they look like a semaphore telegraph, a tower with moveable arms that was used in the 18th and 19th centuries to communicate messages long distances.

Winners of the Nature TTL photography competition.

A giant sinkhole has opened up in Chile and the internet wants to know how many breakfast burritos can fit inside.

We don’t know if trees have brains, but this beautifully detailed new jellyfish proves you don’t have to have a brain to move.

If you liked this issue, please click the “like” button below - it makes me happy and also raises the profile of this newsletter!

As always, so interesting. Are you familiar with the wild walking oats of Israel? Pretty amazing!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NlUparIDfzE

I'm familiar with Mimosa pudica and other species of Impatiens (although I've never encountered the North American species), but I'd never heard of the telegraph plant. My mind is blown.